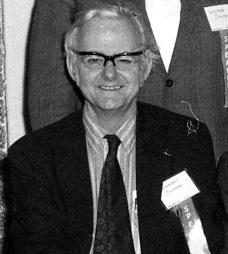

Humphry Osmond (front row seated, far left), with the Paulings and others at a gathering in Tulsa, Oklahoma. June 1972.

Dr. Humphry Fortescue Osmond, while never a direct collaborator of Linus Pauling’s, was nonetheless a professional influence in his life and a friend. Alongside Dr. Abram Hoffer, Osmond helped to establish orthomolecular psychiatry, the precursor to the larger body of work on orthomolecular medicine that consumed Pauling for close to three decades. Later in life, Pauling and Osmond wrote numerous letters back and forth, in which Osmond often shared interesting articles on the uses of vitamin C, schizophrenia, nutrition, and orthomolecular medicine.

Osmond is famous to both the medical community and to the public for related, yet separate reasons. In the field of medicine, Osmond, along with Abram Hoffer, is best known for his work in orthomolecular psychiatry. Working together, the two doctors performed extensive studies on schizophrenic patients in psychiatric hospitals in Saskatchewan, Canada, using niacin (vitamin B3) and ascorbic acid (vitamin C) as potential cures for the disease. Osmond is also known for his work with lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD, in the treatment of alcoholism and as a way for psychiatrists and psychologists to experience something approximating what he believed to be the state that schizophrenics experience as they struggle with their illnesses.

To the public however, Humphry Osmond will forever be known as the man who coined the term “psychedelic” and the man who “turned on,” in the words of the famous LSD advocate Timothy Leary, acclaimed British author Aldous Huxley, a man with whom he developed a close friendship. In the early 1950s, Huxley approached Osmond after reading an article on his research with mescaline; Huxley expressed a desire for Osmond to run a human trial of the drug with Huxley as subject. Osmond wasn’t fond of the proposal, not relishing “the possibility, however remote, of finding a small but discreditable niche in literary history as the man who drove Aldous Huxley mad.” Despite his misgivings, Osmond dosed Huxley with 400 mg of mescaline in 1953. The result was recorded in Huxley’s cult hit The Doors of Perception (1954), a book that both takes its name from William Blake’s poem “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” and inspired the name of the legendary 1960s rock band, The Doors.

Later, when discussing his flight of hallucinogenic fancy, Huxley, writing to Osmond, penned this bit of verse:

To make this mundane world sublime, / take half a gram of phanerothyme.

The word phanerothyme, cobbled together from the Greek, translates roughly to “manifest spirit.”

In response Osmond wrote some poetry of his own, in the process coining a term that soon spread around the world:

To fathom Hell or soar Angelic, / just take a pinch of psychedelic.

Psychedelic - again from Greek etymology - translates to “mind-manifesting.” By 1957 Osmond had introduced the word to the medical community as a way to describe the euphoric, perception-altering, mind-expanding effects of hallucinogenic drugs like LSD, mescaline, DMT, and psilocybin. Previously the only well-known description of this concept was “psychotomimetic,” a mimicry of the symptoms of psychosis.

Humphry Osmond was born in July 1917 in Surrey, England, gaining his primary and secondary education from Haileybury, a long-established boarding school in Hertfordshire. After Haileybury, Osmond earned his medical degree from Guy’s Hospital Medical School, London, in 1942, and from there joined the Royal Navy, commissioning as a surgeon-lieutenant and training to be a ship’s psychiatrist.

After the Second World War concluded in 1945, Osmond returned home and accepted a position as a resident psychiatrist at St. George’s Hospital, Tooting. It was here that he met his future wife, Amy “Jane” Roffey, and his first major research partner, Dr. John Smythies. Together, Smythies and Osmond performed a number of studies in the late 1940s on the chemical composition and effects of the drug mescaline – a hallucinogenic derived from the peyote cactus – having been inspired by the work of Albert Hofmann, who had discovered the hallucinogenic properties of LSD a decade prior.

From their research, Smythies and Osmond hypothesized that because the experience of subjects on mescaline seemingly mimicked the symptoms of schizophrenia, and that because mescaline is structurally related to adrenaline, it could be possible that schizophrenics were over-producing a chemical related to both mescaline and adrenaline. They called this hypothesis, fittingly, the “M-hypothesis.” The idea, when presented to the British psychiatric medical community – which at the time was dominated by Freudian thinking – was not well received. Feeling isolated in the UK, in 1951 Humphry and Jane Osmond, along with John Smythies, immigrated to Canada, where Osmond had been offered a job as the clinical director of the psychiatric hospital in Weyburn, Saskatchewan.

“How to Live with Schizophrenia,” by Abram Hoffer and Humphry Osmond, 1966.

It was at Weyburn that Osmond met Dr. Abram Hoffer, director of psychiatry at the hospital, with whom Osmond would collaborate for the next decade. Working together with the patients at Weyburn and at neighboring hospitals, Osmond and Hoffer developed what became known as the “Hoffer-Osmond Adrenochrome-Hypothesis.” Using the M-hypothesis as their basis, Osmond and Hoffer claimed that it was adrenochrome, a byproduct of adrenaline that is structurally similar to mescaline and other hallucinogens, that schizophrenics were overproducing. In theory, schizophrenics were suffering from their disease either as a result of their bodies producing too much adrenochrome or through an inability to properly metabolize adrenaline.

Working from this hypothesis, Osmond and Hoffer next searched for a way to reduce the overproduction of adrenochrome, hoping to find a cure for schizophrenia as well as additional evidence for their idea. Learning that niacin might limit the production of adrenaline, they decided to dose their schizophrenic patients with “megavitamin” amounts of B3, adding it to their diets in the first double-blind studies ever conducted in the field of psychiatry. The results were encouraging: according to their studies, the recovery rate for the schizophrenics that they treated over the next few years doubled from 35% to 75%.

In addition, the Osmond and Hoffer studies provided data that added to the finding that niacin could reduce cholesterol, a result that was replicated and confirmed by the Mayo Clinic in 1956. This finding is now globally accepted and niacin is presently used in the treatment of high cholesterol all over the world.

An example of Hoffer’s “memos,” October 1976.

In 1967 Linus Pauling read the Osmond and Hoffer studies and, finding the subject interesting enough to pursue further, wrote to the duo asking for more information. The data that he received was eventually included by Pauling alongside his own theories in his seminal paper, “Orthomolecular Psychiatry” (published in Science in 1968) as well as in the book that he co-edited with Dr. David Hawkins, Orthomolecular Psychiatry: Treatment of Schizophrenia (1973). Over time, Pauling expanded his orthomolecular theory from the study of the mind to include the whole body, thus creating the field of orthomolecular medicine.

This initial contact between Drs. Pauling and Osmond led to a nearly thirty-year correspondence between the two men, with Osmond regularly sending to Pauling selected copies of his “memos” - commentaries in which Osmond would paste a news article onto the left side of a sheet of blank paper, then cover the right side and the back with prodigious, elegant essays on the context, significance, and meaning of the article. (These memos were collected into a book, Predicting the Past, and published in 1981). Osmond made special effort to forward to Pauling those memos concerning ways in which orthomolecular medicine was being used around the world as well as any material on mental illnesses.

Exchanges between the two men were often personal as well as professional. For example, after learning of Ava Helen Pauling’s trouble with cataracts, Osmond sent Dr. Pauling any information that he could find on the ocular malady, of which Osmond was also a sufferer. Osmond also wrote letters filled with his thoughts on Pauling’s activism and increasing celebrity, including a letter in which he agreed with Pauling’s negative assessment of physicist Edward Teller, a major advocate for U.S. nuclear armament and the hydrogen bomb, as well as a letter congratulating Pauling on his 1977 appearance on NOVA.

In 1961 Osmond was appointed Director of the Bureau of Research in Neurology and Psychiatry at Princeton University. While there, he continued his research into schizophrenia as a physical illness. In 1970, hallucinogenic drugs like mescaline, LSD, and DMT were declared controlled substances, and studies on the effects of these drugs on psychiatric patients was curtailed.

In 1971 Osmond resigned his position at Princeton and moved to Alabama, where he taught at the University of Alabama, Birmingham as a professor of psychiatry. He worked there alongside his old friend, John Smythies. Osmond also consulted at Bryce Hospital in Tuscaloosa, the oldest and largest in-patient psychiatric hospital in Alabama. He retired from the university and the hospital in 1992. A decade later, by then an octogenarian, Osmond granted an interview for a documentary on the history of LSD, titled “Hofmann’s Potion.” Not long after, in February 2004, Osmond died of natural causes at his daughter’s home in Appleton, Wisconsin. Abram Hoffer wrote an obituary on the event of Osmond’s passing, which was featured in the British newspaper, The Guardian.

Some of Humphry Osmond’s more well-known books include The Chemical Basis of Clinical Psychiatry (with Abram Hoffer, 1960); How to Live with Schizophrenia (with Hoffer, 1966); Psychedelics: The Uses and Implications of Hallucinogenic Drugs (with Bernard Aaronson, 1970); and Models of Madness, Models of Medicine (with Miriam Siegler, 1974). A complete bibliography of his works can be found here.