By Alan Bean

By Alan Bean

Mineral Wells is a Texas town of 17,000 a little over fifty miles due west of Fort Worth. The Texas legislature passed a budget for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice that will require the closure of two prisons and the Mineral Wells Unit is on the list. Local officials say they will fight to the last ditch and the last breath to keep their precious prison.

This isn’t about public safety–the state of Texas has decided it doesn’t need the prison–it’s about jobs.

All of which raises a disturbing question. Was the prison boom that transformed Texas in the 1990s about pork barrel politics rather than public safety?

Back in the day, nobody wanted a prison in their back yard; but hard times in the hinterland changed “you’re not building a prison in my back yard,” to “we’ll provide generous subsidies if somebody–the state or a private prison company–is willing to build us a big house.” In towns like Mineral Wells and Tulia, the war on drugs, tough on crime politics and prison construction were all about helping little towns survive an agricultural crisis that started in the mid-1970s and shows no signs of letting up.

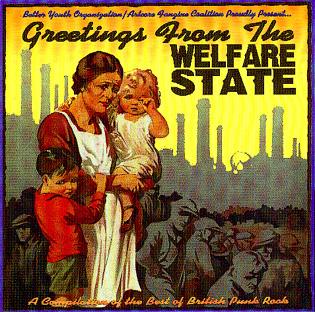

In the process, small-government Texas became the nation’s biggest welfare state.

It is unwise and immoral to base public safety decisions on the economic needs of isolated farming communities, but that is precisely what we have done. Listen to the public officials in the Star-Telegram article below lamenting the loss of their darling prison and you realize that our nation’s great prison boom spread a horrible case of welfare dependency across the American heartland.

Mineral Wells vows to fight devastating closure of prison

BY ANNA M. TINSLEY

The uncertainty is troubling many in Mineral Wells.

The question that continues to linger is whether the Mineral Wells Pre-Parole Transfer Facility — a 2,100-bed, privately run minimum-security prison — will close.

State lawmakers last month passed a budget that reduces jail bed capacity by $97.3 million, which is exactly the amount that would be saved if both the Mineral Wells facility and the Dawson State Jail in Dallas were shuttered.

But the budget, which still must be approved by the state comptroller and Gov. Rick Perry, no longer specifically names the Mineral Wells facility as one that must close, due to legislative maneuvering by state Reps. Phil King, R-Weatherford, and Jim Keffer, R-Eastland.

Instead, it calls on prison officials, rather than lawmakers, to decide which prisons to shutter and to base that decision on economic factors.

“It’s not over yet,” King said. “But it’s still an uphill fight.”

Mineral Wells officials say closing the prison — one of the largest employers in the community of around 17,000 — would devastate the small city, putting more than 200 people out of work and drying up the flow of millions of dollars each year from the Nashville-based Corrections Corporation of America.

“We’re going to fight this to the bitter end,” Mineral Wells Mayor Mike Allen said. “We will fully support CCA and do our best to keep it here.”

Some lawmakers say their decision is solely based on finding the best use for taxpayer dollars.

“I understand the concerns of Mineral Wells’ leadership,” said state Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston, who heads the Senate Criminal Justice Committee. “But we have to do what’s best for the state of Texas.”

Now it’s up to officials at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to determine this summer which facilities to close to reduce the prison budget by $97.3 million.

Their next two meetings are June 21 and Aug. 23.

Longtime concerns

State officials say this facility about 50 miles west of Fort Worth, which is in Parker and Palo Pinto counties, has been on their radar for years.

The sprawling prison — bounded mostly by 50-foot-tall netting and a chain-link fence topped with razor wire — is in an industrial park once known as Fort Wolters, an Army camp that became an Air Force base and ultimately an Army helicopter school.

The base was deactivated in 1973. But by 1989, as the state faced lawsuits and complaints about prison overcrowding, a number of the buildings at Fort Wolters were converted into a pre-parole transfer facility.

Initially it was a pre-release program for inmates who had been involved with drugs and alcohol, but Whitmire said it hasn’t been used for that in years. Mineral Wells officials say it does prepare inmates before they are released.

Through the years, various problems brought the prison to the attention of lawmakers, including a crackdown on cellphones in prisons in 2008.

After people repeatedly tried to throw contraband — cigarettes, cologne, prepaid cellphones, drugs — into the prison yard there, officials installed the large net around the building.

“This is not a prison,” Whitmire said. “TDCJ has always had to be cautious about inmates placed there. … We’ve got about 12,000 empty beds in state prisons. Why would we pay $50 million for private beds when we have empty state beds?”

King said he believes many of the problems in Mineral Wells have been fixed.

“They really aren’t an issue anymore,” he said.

Looking ahead

Whitmire had pushed to formally strip the CCA money in the state budget, but agreed to a plan that doesn’t specify which two prisons would close, instead letting TDCJ officials choose which facilities to shutter.

“The agency has not yet identified any specific facility for closure at this time,” said Jason Clark, a TDCJ spokesman. “The budget is typically signed by mid-June. The decision will be made sometime after that.

“Mineral Wells’ contract ends Aug. 31.”

And Perry has until June 16 to sign or veto bills or they automatically become law.

Whitmire said that state officials will work to relocate workers at any prison that closes to another prison in Texas.

For now, CCA officials say they will try to discuss the issue with prison officials before any decision is made.

“Until we have those conversations, we cannot speculate on what the future may hold for Mineral Wells,” said Steve Owen, senior director of public affairs for CCA. “We are proud, however, of our very talented and dedicated staff and remain thankful for the local and state officials who have been advocating tirelessly for the more than 230 professionals employed by CCA at Mineral Wells.”

Local officials have estimated that the prison has an $11.7 million annual payroll, pays nearly $2 million each year in utilities and more than $75,000 in local property taxes and buys nearly $250,000 dollars in local goods and services.

Their estimates show the daily cost of housing an inmate at the Mineral Wells facility is $34.80, compared with $42.90 at similar state-owned prisons.

King said he and Keffer are sending a letter to TDCJ officials, asking to be notified when prison closure discussions begin so they can weigh in on the issue.

“There are public prisons that cost a lot more to run than the private prison,” King said. “So why shut down the private prison if it operates at significantly less cost than public prisons?”

Allen said he and other city officials are trying to figure out how to help CCA.

“The main thing we were hoping for during the session is that TDCJ would make this decision instead of the Legislature,” Allen said. “Hopefully they’ll look at the economic impact, the efficiencies of the prison … and how it is less expensive than a state prison.

“Pray for us.”

Anna M. Tinsley, 817-390-7610 Twitter: @annatinsley