Americans in the Russian Civil War (source)

While the 110th Infantry battled for survival in France, the 339th Infantry waited across the English Channel to join them. Dubbed "Detroit's Own," the 339th consisted of Michigan and Wisconsin recruits under Colonel George Stewart. They little suspected their fate until Lieutenant Harry A. Mead, commanding Company A, had a chance encounter with Lowell Thomas, returning from his fateful rendezvous with T.E. Lawrence. Thomas shared with Mead a rumor, gleaned from conversation with Allied generals in Paris, that the 339th would deploy not to France but far-off Russia.Mead scarcely credited Thomas's warning. He knew of the previous year's Russian Revolution, which replaced tsarist autocracy with Communist dictatorship, and removed Russia from the war. But what had that to do with the United States? But the 339th soon found their British Enfield rifles swapped with Russian Mosin-Nagants, followed by winter clothes markedly inappropriate for a French summer. Within months the regiment, nicknamed the "Polar Bear Expedition," received orders sending them to Arkhangelsk, a port city in northwestern Russia.

The Polar Bears became pawns in an utterly confused operation. In April 1918, British and French troops under General Sir Frederick C. Poole occupied Arkhangelsk and Murmansk, along with American sailors from the USS Olympia. Their stated goals were to revive the Eastern Front under Allied aegis, and to recover stockpiles of weapons sent to Russia. Winston Churchill, Britain's Minister of Munitions, urged his colleagues to "reconstitute the fighting front in the East...If we cannot...no end can be discerned to the war."

Sailors from the Olympia land in Arkangelsk (source)

Elsewhere, Churchill confided a less noble intention of "strangling Bolshevism in its cradle." Like most Western statesmen, he viewed Vladimir Lenin's new regime with abject horror, hoping to crush it before Communism took root. Allied diplomats in Russia echoed his sentiments; American Ambassador David Francis savaged Lenin as "a man with the brain of a sage and the heart of a monster," while British Minister Sir George Buchanan proclaimed Bolshevism "the root of all evils from which Russia was suffering." Only Jacques Sadoul of France urged moderation, chastising colleagues who "persist in denying that the world turns."In fact, the Allies and Bolsheviks initially became uneasy partners against German armies menacing the region. Leon Trotsky directed local Bolsheviks to "accept any and all assistance from the Allied missions" to prevent "German plunderers" from seizing Northwest Russia. Yet within months, tensions mounted as Poole's force increased. President Woodrow Wilson, initially reluctant to intervene in Russia, authorized the dispatch of American troops. By summer, the Allies were in Northwest Russia to stay, and warfare with Bolshevism became inevitable.

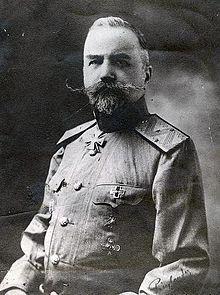

General Poole mishandled the situation from the start. He initially encouraged a Menshevik government under Nikolai Chaikovsky in North Russia, only to replace him with Yevgeny Miller, a reactionary Tsarist general. British Captain George Chaplin, justified this coup d'etat by commenting, "I see no use for any government here anyway." Worse, "Poole was noted for his colonial approach to Russians," writes historian Robert L. Willett, alienating the locals through condescension and arrogance. Poole thus lost the battle for Russian hearts and minds before it properly began.

General Miller, redoubtable reactionary (source)

Nor did Poole show firm logistical sense. He dispatched troops deep into the Russian heartland, thrusting at railroad depots and arms stockades; dozens of men were lost in hopeless, pointless fights along the way. American Ambassador Francis encouraged Poole's schemes, writing that he would "encourage American troops to proceed to such points in the interior as...Petrograd and Moscow, [where] are stored war supplies which the Soviet government... transferred from Archangel." By such incredible mental legerdemain did their mission transform into a war of conquest.The 339th reached Arkhangelsk arrived in early September. Disoriented by their long voyage and wrecked with an outbreak of Spanish influenza, they found a snow-bound city, forbiddingly beautiful in perpetual twilight, yet overrun by refugees and foreign soldiers. The townspeople were friendly, but the Americans immediately butted heads with their British allies, who showed little compassion for flu-stricken Americans, 63 of whom died within a month of their arrival. When the American Red Cross set up their own hospital, the British protested their flying the Stars and Stripes; an American officer had to dispatch sentries to prevent them from removing it.

Anglo-American relations were touchy in that era, whether in the Somme trenches or the halls of Versailles, but rarely more than in North Russia. The doughboys chafed at General Poole's bombastic proclamations, the peremptory attitude of his subordinates (stories arose that junior officers carried epaulets to ensure they always outranked Americans) and a general lack of respect. During one skirmish, poorly aimed British artillery killed or wounded several Americans. The British commander, upon discovering his mistake, coolly sipped some whiskey and ordered his gunners to reset coordinates. Such accidents were inevitable in war, yet exacerbated the mutual ill-feeling.

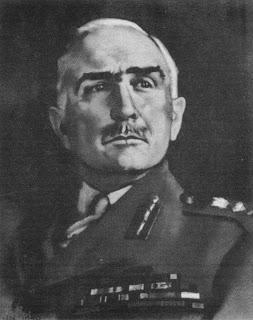

Sir Edmund Ironside (source)

The Americans made an exception for Major General Sir Edmund Ironside, who relieved Poole in November. A decorated hero from France (and much later, Chief of the Imperial General Staff), Ironside's fortitude and affability, frequently traveling to the front and chatting with troops, made him popular with the Yanks: Captain Joel R. Moore proclaimed him "every inch of his six foot-four a man and a soldier, par excellence." Ironside commanded both affection and respect, and his efforts did much to smooth the rocky relations between doughboy and Tommy.Equipment remained a headache. The Mosin-Nagants they carried frequently jammed or misfired; Private Donald E. Carey dismissed them as "worthless weapons" and quipped, "no wonder [Russia] lost the war." They received these sub-par rifles in hope of using Russian stockpiles of ammunition, which the Bolsheviks had already plundered. Americans also used British Lewis and Vickers machine guns, which were water-cooled and frequently froze in extreme temperatures. "Can you imagine using a water-cooled up in that climate where for twelve straight weeks it never got above fifty below zero?" complained Russell Hershberger.

Nor did the Americans appreciate their second-rate British rations, their ill-fitting Shackleton boots (designed by the Antarctic explorer) and chronic lack of material. At least the doughboys received warm coats and hats, which in such frigid temperatures (30 below zero was common) was a strict necessity. Perhaps it's best that they never learned of a gang of crooked commissary officers who purloined stockpiles of supplies, selling them to Russian black marketers at outrageous prices. The Bolsheviks (or "Bolos," per their nickname) often seemed the least of their worries.

Making the most of it (source)

The Americans easily befriended the Russian peasants. Though occasionally repulsed by their foul-smelling, ubiquitous fish oil, the Yanks found them hardworking, resourceful and honest. One Russian told Ralph Albertson that he liked Americans "because they treat us like equals...because they are good to the Russian people." Friendships blossomed, along with romance; at least eight Americans married local girls during the occupation. Doughboys also befriended French poilus, who overcame language barriers through wine and battlefield courage, and respected the no-nonsense Australians and the deadly skill of Canadian artillerymen.Both Poole and Ironside sent large detachments of Allied troops into the Russian interior, with poor coordination between different units. The initial expedition, Force A initially consisted of French troops and Russian conscripts, the so-called "Anglo-Slavic Battalion" - all under the command of British Colonel Sutherland. Pushing south, they seized numerous towns along the railroad before meeting heavy resistance at Obozerskaya and a railroad depot called Verst 464. Troops of the 339th's Company I saw heavy action on September 16th, where they repulsed a Bolshevik assault on Verst 464, then drove them off with a bayonet charge.

A follow-up operation stalled when American troops from Companies I, L and M became hopelessly lost. Colonel Sutherland had sent them without proper maps, and many became lost in deep forest bogs. They faced shellfire from Russian armored trains traveling down the lines; when the Americans attempted to return fire, their heavy mortars sunk into the swamp. "We ended up a swamp, knee-deep in water," summarized Lt. Albert May. "We found no positions. When the artillery opened up, we were in front of their barrage."

Doughboys with a captured "Bolo" sword (source)

Getting lost in the woods proved a blessing in disguise, as shown when a mixed Franco-American force attacked a Bolshevik camp near Plesetskaya on September 29th. The well-entrenched Bolsheviks turned back the allies with machine gun fire, forcing them to take cover near a railroad bridge. It's here that Colonel Sutherland victimized his allies with friendly fire, turning a debacle into a disaster. By mid-October, as the first snows fell, the Allies finally abandoned the offensive, constructed wooden blockhouses and outposts around the railroad.The campaign's largest battle began at Toulgas on November 11th, further east along the Dvina River. Company B of the 339th, under Captain Robert Boyd, was stationed at this small town intersected by the Dvina, along with Canadian artillery. American troops on the north side of the Dvina were breakfasting when they came under bombardment from Bolshevik gunboats. Soon a force of 500 Bolsheviks appeared to the west; before the Americans could react, another materialized from the South. Shouting "Hurrah!" the Red troops charged at the heavily outnumbered Americans.

Lt. Henry Dennis rallied a small force at the blockhouses outside the town, but they were swiftly overrun. They fled across a bridge into Lower Toulgas, braving shellfire from the gunboats; miraculously, only Private Leo Gasper fell in the action. Recovering from their initial shock, the Americans checked the Bolshevik infantry with close-range machine gun fire, while their Canadian allies foiled a flank attack. At this crucial moment, a company of Royal Scots arrived and helped check the Russian advance. The Russian commander overran an Allied hospital, threatening to shoot the wounded until his mistress intervened.

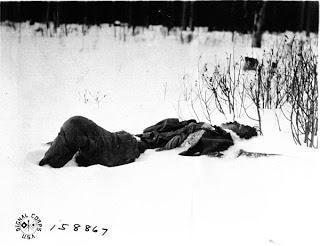

A Bolshevik casualty (source)

Having suffered heavy casualties, the Russians were reluctant to press their attack; they continued shelling American positions with artillery for several days, but never launched another full-scale assault. During the stalemate, Lt. Dennis led a squad of infantrymen on a dangerous mission to Upper Toulgas, eliminating dozens of Russian snipers. Eventually the Bolsheviks ceased their barrage and withdrew, leaving behind nearly 500 killed or wounded, in exchange for 30 Allied dead and 100 injured.The Allies achieved a hard-fought victory, but decided to clear Upper Toulgas in a brutal fashion. With snipers continuing to plague his men, on November 15th Boyd ordered Sergeant Silver K. Parris to burn that segment of the village. "My heart ached to have the women fall down at my feet and grab my legs to kiss my hand and beg me not to do it," Parris admitted. "But orders were orders...[we] went across that field, so I done my duty (sic)".

The fighting at Toulgas coincided with Armistice Day, ending the war with Germany. Those in Russia aware of the situation grasped the bitter irony. One officer, Ralph Albertson, encountered angry Americans in an Arkhangelsk hospital. "The armistice is signed, why are we fighting?" one demanded. Another asked, "We don't want Russia, what have we against the Bolsheviki?" Albertson had no answers for them, but neither did Woodrow Wilson, Colonel Stewart or anyone else.

Polar Bears at the front (source)

As the occupation dragged on through 1919, fighting continued (including a large battle at Bolshie Ozerki) and the conflict showed no signs of winding down. Rumbles of discontent spread among the Polar Bears; self-inflicted injuries proliferated, and questions of why they were fighting grew louder. On March 15th, several of them presented a mutinous position insisting "we positively refuse to advance on the Bolo lines including patrols," proclaiming "our object in Russia has been accomplished." Sympathetic American officers talked them out of outright mutiny; British, French and White Russian units weren't so lucky.Colonel Stewart had long since alienated his men, spending his time at Arkhangelsk, rarely visiting the front and forgetting his officers' names. He was relieved by Brigadier General Wilds P. Richardson, who did his best to restore discipline and raise morale. He spoke stirringly, insisting that their expedition was "to do a certain duty, determined by the highest authority in our country" and that their fighting was, somehow, an extension of World War I. Historian E.M. Halliday comments that the Polar Bears "listened politely, and thought of home."

At home, more Americans started thinking of the Polar Bears. Some were radicals like Helen Keller, who attacked Wilson for "fighting the Russian people half-secretly and in the dark with the lie of democracy on [his] lips." More Establishment voices also heard complaints: Michigan Senator Charles Townsend received hundreds of letters from his constituents, complaining that "their boys and their husbands were in that God-forsaken country practically lost." General Peyton March, Army Chief of Staff, received a cable imploring him to "For God's sake, say something and do something!"

American dead in North Russia (source)

Finally, in July 1919 the 339th left Arkhangelsk amidst little fanfare. The British remained for several further months, fighting bloody actions in the Russian hinterland before they, too, lost hope in their chances. This left the hapless General Miller, whose minuscule army lasted until February 1920, whereupon he and 800 survivors evacuated the region. One Russian woman, whose family had sided with the Allies, reflected bitterly on the expedition: "Why did they come at all? We shall pay a bitter price for this." Indeed, some 30,000 North Russians suspected of collaboration perished at Bolshevik hands within the following year.The Polar Bears couldn't have answered, unsure themselves why 235 of them had perished, and 1,200 others endured ten months of anguish. Russell Hershberger reckoned that "we evacuated because they wanted to get us out of the country"; indeed, the Allied intervention, with its limited force and muddled objectives, sparked more resentment (and atrocities) among Russians than success. While greeted rapturously upon their return home, the Polar Bears were forgotten with shocking swiftness. Their exploits remain so obscure that Richard Pipes, an American historian writing in 1995, could claim that "the Americans and the Japanese never engaged the Red Army."

Pipes' amnesia would have dismayed veterans of the 339th. However futile or muddled their expedition seemed, the Polar Bears retained a fierce pride in their exploits. "They stuck and fought, suffering through the bitter months of winter below the Article Circle, where the winter days is in minutes and the night seems a week," rhapsodized Lt. John Commons. "And there is not one who is not proud that he was once a sidekicker and a buddy to some of those fine fellows of the various units who unselfishly and gladly gave the last a man has to give." Perhaps there's no better epitaph for soldiers anywhere.

This article draws upon: Ralph Albertson, Fighting Without a War (1920; online here); E.M. Halliday, The Ignorant Armies (1958; later republished as When Hell Froze Over); Lewis H. Jahns, etc. The History of the American Expedition Fighting the Bolsheviki (1920; online here), which provided most of the images; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War (1989); and Robert L. Willett, Russian Sideshow: America's Undeclared War, 1918-1920 (2003). Richard Pipes' comment comes from his work Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime (1995).

Other articles on World War I and the Age of Wilson:

- The American Protective League and the War on Slackers, 1917-1919

- The Eastern Front, 1914-1917 (1975, Norman Stone)

- The Guns of August (1962, Barbara W. Tuchman)

- The Hun's Shadow in America, 1917-1918

- Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I (2014, Alexander Watson)

- The Siege (1970, Russell Braddon)

- Somerset County's Men of Iron in the Great War