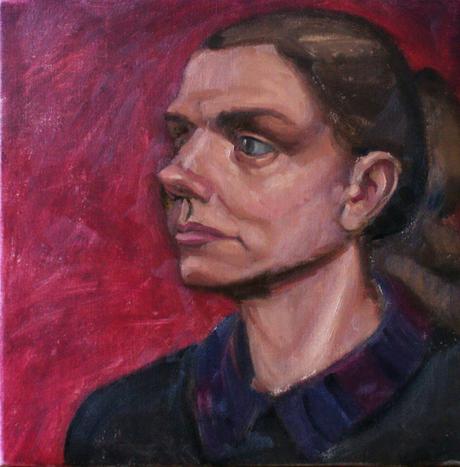

Steffi (2.5 hour oil sketch)

There is an inherent tension between a painter’s sensory encounters with the world and her own habits. As I push myself to paint and draw with increasing intensity, I am driven by conflicting impulses to improve and to investigate. Improvement requires repetition and practice, but investigation tends to tear down all this dedicated work. My understanding and my repertoire broaden and deepen with investigation, but my improvement stagnates, or worse, everything I was so anxiously holding together comes completely undone.

In moments of doubt, I return to trusty Robert Nelson (2010: 121), who reassures me, ‘We all have habits.’ In his judicious way, he writes that habits have their advantages and disadvantages. Hard-earned habits through which we have assimilated knowledge ‘are at the root of our fluency, our readiness, our comfort in tackling the lofty task of representation by the senses and the hand’ (2010: 121). Without such dependable tools, we would face each new picture completely disarmed, unprepared and overwhelmed at the formidable task before us. And these tools, once acquired, need maintenance, and permit refinement, and generally positively benefit from regular and sustained attention.

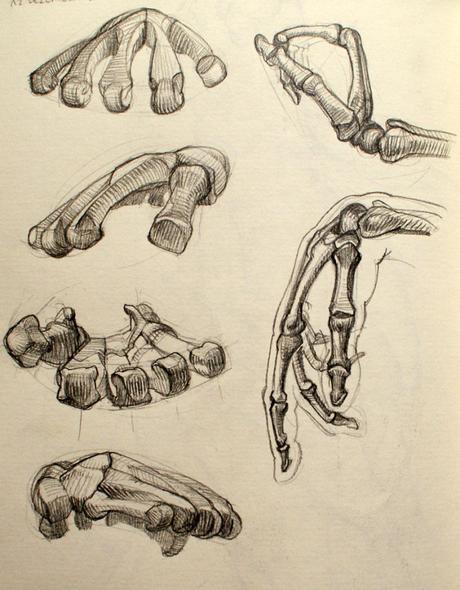

Copy after Rubens, Selbstbildnis

My attention has turned rather feverishly toward copying: with religious zeal I am flooding pages and pages of my sketchbook with wholly unoriginal drawings; copies of old master paintings, copies of anatomy drawings. It can be a very passive way to draw: the burden of having an original idea or making an original investigation is gently taken away from me. It could yet be investigative—with due concentration, I could, through such copies, begin to unpack the decisions of the artists who produced the originals. And sometimes I do. But sometimes I just copy, pleasantly pulling my pencil across the page, enjoying the motion, and daydreaming a bit. This pleasure drawing has its advantages: the habit of going to the gallery, of plunging into the anatomy book, means I give time to some form of drawing with dedicated regularity. And each time I start, there is the possibility that my brain will actively engage. The act itself, begun unthinkingly, can trigger thought.

Copies after Gottfried Bammes

But as I practice and practice, investing in my favoured media, becoming more accustomed to their limitations (and my own), I fall into patterns of working, and the patterns lead to ruts and their accompanying frustration. What looks like fluency and adeptness and confidence to outsiders actually feels like being stuck. Showmanship can get in the way of honest engagement with the physical world, and instead of turning afresh to sensory experience we rely on mechanistic motions. ‘By and large,’ writes Nelson (2010: 130), ‘a mechanical application of directional gestures is about superficially looking flash or stylistically sophisticated, or emotionally confident, or artistically full of panache and bravura rather than serving exploration and curiosity.’

Pregnant lady (oil sketch, 2 hours)

And so despite the benefits and even necessity of forming (hopefully good) habits, Nelson cautions the painter against a ‘mechanistic’ approach, a mindless, formula-driven mode of working that crowds out the possibility of active picture-making. ‘Making art from habit,’ he writes (2010: 121), ‘has questionable consequences.’ For we are not simply producing polished products, little one-man factories. We are constructing pictures by means of a certain kind of logic: an organic, integrative logic that brings together all of the knowledge we have collected about tone and color and gesture and space and texture and so on (2010: 117; 124). Though we can separate out each element and map out distinct stages of a painting through time, the most thoughtful pictures are those that weave everything together, and this unity, argues Nelson, has its origin in the sensory experience, and not in well-oiled mechanistic habits. ‘All of the painting is about building, constructing forms, constructing spatial relationships and constructing rapports in colour; and these are integral to looking, seeing, remembering and imagining’ (2010: 124).

‘The painting conceived in this way replicates, on a somewhat clumsy and grandiose scale, the process of perception itself, constantly gauging relationships and skipping all over the field in order to assess the spatial calibre of what is observed.’ (2010: 122-3)

Such alertness means we have to sacrifice some of our hard-won ability. Confronted with a real subject, with differing light conditions, with the air shimmering at the horizons of the forms, with compositionally compelling shapes that compete with descriptive and meaty forms, we find our assortment of tools to be lacking. What served us well in countless previous situations is not up to the task at hand. The world is ever lavishing new sensory experiences upon us, and the genuinely curious painter responds to the experience, indulges his senses, rather than repeating his well-rehearsed performance.

And this is the tightrope we walk: trying to furnish ourselves with tuned and ready instruments that are fit for the sensory experiences we are constantly greeted by, but remaining open to those experiences, adaptive, and seriously investigating them. It’s no good to throw away what we’ve learned and start from zero every time, but we must also open our eyes and engage our brains. Nelson (2010: 129), ever eloquent, describes the clash of habits entrenched in the body and the inquisitive encounter with the world thus:

‘The brush is constantly invoking the seen: it requires a certain nerve, a zeal for finding out what is perceived or imaginatively solicited and then for correcting what is conjectured. Unless somehow designed with a Platonic conceptual remove, it is all chop and change at a sensory and intellectual level. Add to that the co-ordination of the hand by impulses, the way that the process draws upon the muscles and uses the body: it demands a stance before the canvas and a rhythm of subliminal choreographic vibrations.’

It would be foolish to be dogmatic about either emphasis, for both are crucial. Each destroys the other, but only to rebuild it more firmly, and more enmeshed with the other.

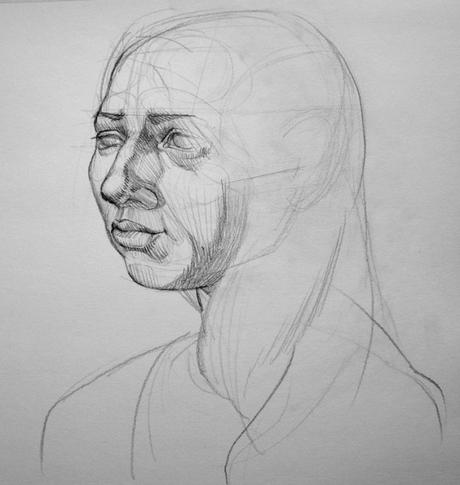

American girl (2.5 hour oil sketch)

Nelson, Robert. 2010. The Visual Language of Painting: An aesthetic analysis of representational technique. Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne.