by Alessandra Morelli / Minority Voices

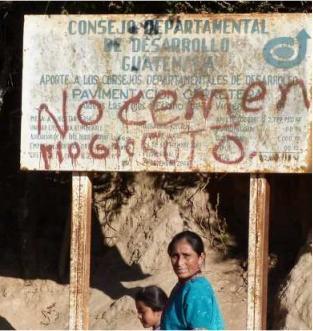

Isabel Turuy Patzan visiting the MRG office. Credit: MRG/Alessandra Morelli

San Juan Sacatapéquez is a Guatemalan town, rich in natural resources and biodiversity, where indigenous Maya Kaqchikel form 82 per cent of the population. In 2006, the government granted concessions to the Guatemalan company CEMPRO (Cemento Progreso S.A.) to build a quarry and a cement factory in the area, and a new road cutting through communal land. Indigenous communities from San Juan were not consulted or previously informed about the works, as is required under international standards.

Since the mega project started, a climate of violence and tension has characterized the region. In 2008 a State of Emergency was declared for several months and the community suffered abuses and human rights vilations at the hands of both state and non-state actors. In response to the brutal attacks, legal accusations, arrest warrants and detention of Kaqchikel community members, the 12 Communities in Resistance was created – a social movement in opposition to the project.

On 19th May 2014 Isabel Turuy Patzan, a representative of the 12 Communities in Resistance since 2009, visited MRG’s offices in London as part of a speaking tour organised by Peace Brigades International (PBI) UK.

The current situation

Since the concessions were granted, the entire community has fallen victim to a process of expropriation, violations of rights and persecution, according to Patzan. People have been manipulated and documents forged and the project is detrimental to the community and biased in favour of CEMPRO, he says. For example, although the communities already have access to roads to the capital city and others are abandoned or in bad condition, the construction of a new road has been proposed. This does not respond to the infrastructural needs of the community, who see the plan as an attempt to dispossess them of their land.

Many complaints have been filed for abuses suffered by the population, but no support has been received from the Guatemalan justice system, which does not apply its jurisdiction evenly, says Patzan. He adds that CEMPRO is using a twofold strategy based on psychological and physical violence to consolidate its presence in the area. On the one hand, the company is using ex-military groups who train people to attack and intimidate the community; on the other hand, it accuses the representatives of the indigenous communities of violent actions.

The process of criminalization – 86 people from San Juan have been arrested and detained so far – is leading to further difficulties and economic hardship for the community. In fact, although the communitiy is organising collections to support the detainees and their relatives, the costs are just too high for a poor region in which the people’s livelihoods depend on agriculture and flower cultivation.

San Juan before and after CEMPRO

Over the past seven years life in San Juan has totally changed from a social, economic and cultural point of view. Before the cement plant project started, the communities were living in peace and had a good relationship with the police. However, the current division between groups in favour and those against the factory is reflected in everyday life; members of divided families tend to exclude each other when weddings or similar festivities are celebrated, for example.

Religious and traditional customs have also been altered. The three main sacred places in San Gabriel – an area within San Juan – have been privatised and put under the strict control of private security forces who deny indigenous people access to this area where they used to pray and carry out their religious activities.

80 per cent of the population of San Juan are farmers dedicated to agriculture and flower cultivation who have been seriously affected by the dust emissions produced by the cement plant. Due to damage to the local economy, the other 20 per cent of the population moved to the capital city to look for jobs, generating additional expenses for the families trying to support them.

The impact on homes and infrastructure is of concern too. Houses tremble when mine machinery is in use and some homes are at risk of collapse since 84 hectares of forest was felled to make way for the plant. This phenomenon is particularly affecting the communities Trojes I and II, who are subjected to continuous noise and dust because they are directly adjacent to the area where the company operates.

The communities demand respect for human rights

CEMPRO and the Guatemalan government claimed the project would bring growth and development. But Patzan talks of damage to the environment, deaths, physical attacks, destruction of resources and expropriation of lands. No employment has been created as indigenous people do not have the required skills and qualifications for jobs at CEMPRO.

The 12 Communities in Resistance firmly oppose the CEMPRO project and demand respect for human and indigenous peoples’ rights. They also require that the company guarantee health, safety, access to water and sacred places, use of natural resources to practice agriculture and a new environmental impact study to be carried out.

As a 2007 referendum demonstrated, the majority of the community strongly oppose the project: 95 per cent of the population recognize the risk of contamination, water shortages, and destruction of all those activities sustaining the local economy, while the remaining 5 per cent – convinced by the slogan of development – support the construction of the cement factory and accuse the movement of denying San Juan an economic opportunity.

The opposing communities are not against investment, but they do contest those activities which destroy the natural environment. In fact, as Mr. Patzan points out, development plans should be managed by the government and consist of improving education, health and infrastructure. Unfortunately, in Guatemala, not only does a sustainable development policy not exist, but since 2006 every request for its existence by San Juan communities has been stopped by the authorities in order to convince the population to accept CEMPRO’s project. While the communities have been further excluded and discriminated against, the company has been supported both by the government and the Guatemalan mass media, which launched a smear campaign against the resistance movement. Indeed, the media has given a misleading picture of the events in San Juan by portraying members of indigenous communities as subversives and terrorists in order to discredit their fight.

The future of San Juan

Although Guatemala has ratified several international human rights conventions, there are a lot of political and economic interests which make compliance to international treaties less of a priority than economic investments. According to the communities, both CEMPRO and the Guatemalan government are responsible and liable for the conflict in San Juan.

The communities are engaged in this battle to see economic, social and cultural rights respected and fully implemented, not only at a domestic level, but also at an international level. In fact, in November 2013 they filed a complaint against the criminalisation of civil protest before the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights.

In spite of all their efforts, the solution is still far away. However, as Mr. Patzan clearly states, “The fact that the law is not entirely respected and implemented is another reason for not giving up. The movement does not have a vision for the future because it’s still fighting to save its present. The 12 Communities are still in resistance whereas the company hasn’t finished building the factory. The fight is not over, but, as long as people’s solidarity and moral support is alive, 95 per cent of the population is keen to defend the territory and their rights.”

Too many people without a voice need to be heard and, according to Patzan, “They must be prevented from experiencing what their ancestors went through when they were exploited and treated as slaves by large landowners.”