Evolutionary psychology (EP) attempts to understand the evolution of our psychology. No surprises there. It's an important field that could shed a lot of light on both ourselves and our ancestors. Unfortunately it's a field rife with issues; primarily it's use of unrepresentative samples. It's hard to draw conclusions about all of humans (and our evolution) when you only study Westerners.

Over the past few weeks I've been exploring this problem. In part 1 I revealed the vast majority of EP research relied on Western (or WEIRD) samples. In part 2 I discussed whether or not evolutionary psychologists had addressed this problem in recent years (answer: they've talked about it a lot, yet the use of WEIRD samples has not declined).

Today is the third and final installment: why all of this matters.

The problem

Sure, evolutionary psychology uses a lot of WEIRD samples. But does this matter? I mean, Westerners aren't representative of humanity as a whole ( being more easily fooled by illusions, for example) but are they different enough to invalidate EP research that examines them? Have I discovered a real problem in my first two posts, or am I making a mountain out of a mole hill?

That's the issue I wanted to examine in the final part of my research. If I do research on WEIRD people, can I generalise those results to all humans or not? One easy way of examining this would be simply to look at how often research on non-WEIRD people contradicts research on WEIRD people.

Unfortunately this is not a perfect way of testing this, given how complex human psychology is. Sure, Westerners may respond to optical illusions differently, but you can't really use to that to predict whether their fear of snakes is universal (and so maybe evolved) or not.

There's also issues surrounding publication bias. Research which simply repeats a previous study is a lot less likely to get published than new research. Similarly, research with negative results is also less likely to see the light of day. These create the " file-drawer effect ", which can make it very hard to reliably say how often WEIRD results are challenged by non-WEIRD ones.

In short, take the results presented below with a pinch of salt. I still think they're important and worth discussing, but it's unlikely this is the final word on the subject.

The aforementioned salty results

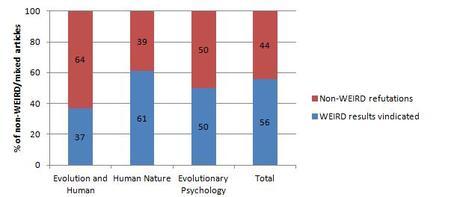

Hopefully by now you know the drill: I examined research published in several EP journals from 2003 - 2007 (and in 2013), examining how much of it used WEIRD samples and how much didn't. When looking at the non-WEIRD research, I then examined whether or not it challenged or vindicated research previously done on WEIRD samples.

The result? WEIRD results were actually vindicated by non-WEIRD research in the majority of cases....by a whisker.

In total, 56% of non-WEIRD research supported WEIRD conclusions. Given ~75% of EP research is done on WEIRD samples, if you extrapolated this data (which, as I mentioned earlier, is problematic) it may well be that 1/3 of all EP research is just wrong. Invalidated by the use of unrepresentative samples.

In short, the issues surrounding WEIRD research is not simply (for want of a better word) academic. It represents a real, significant problem that could be undermining a large swathe of evolutionary psychology. Despite that there's no evidence the field is fixing itself. Examining data over the past few years reveals no significant change in the use of unrepresentative samples.

No positive spin or joke to close out on. Evolutionary psychology has a major problem. It isn't getting better.

It needs to.