At last we review Fritz Lang's Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922). Four-and-a-half hours long, leisurely paced and heavily stylized, it's tough going for those not attuned to silent cinema. Yet Dr. Mabuse rewards persistence viewers, both for its influence and as an absorbing epic.

At last we review Fritz Lang's Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922). Four-and-a-half hours long, leisurely paced and heavily stylized, it's tough going for those not attuned to silent cinema. Yet Dr. Mabuse rewards persistence viewers, both for its influence and as an absorbing epic.Dr. Mabuse (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) is a renowned psychiatrist, eccentrically interested in mesmerism. He moonlights as a master criminal, using a web of henchmen, myriad disguises and hypnotic persuasion to sew chaos. Having rigged the stock exchange, Mabuse tries entrapping Englishman Peter Hull (Paul Richter) for money, then kidnaps Countess Told (Gertrude Welker). Soon Inspector Wenk (Bernhard Goetzke) is on Mabuse's tail despite lack of evidence. Can the straight-laced cop unravel Mabuse's nefarious scheme?

Novelist Norbert Jacques intended Mabuse as metaphor of postwar Germany, which Lang's film encourages. Dr. Mabuse opens with its villain manipulating the stock market: this during Weimar's hyperinflation, reaching 4.2 trillion marks per US dollar by 1923. It also satirizes German decadence and obsession with mystics like Erik Jan Hanussen. And Mabuse's befuddled Weck channels Weimar's ineffectual authorities, helpless as the Freikorps and Spartacists battled in the streets. Lang expanded this in M, with Berlin's underworld hunting a serial killer, and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, remaking Mabuse as Hitler analog.

Subtext aside, Mabuse's a fascinating creation. On the surface he's a cunning Mafia chief, insulating himself through layers of underlings. He uses both force and cunning to effectuate his plans: three grotesque henchmen, blind counterfeiters, his devoted moll Cara Carozza (Aud Egede-Nissen). But he's also a hypnotist, persuading victims to cheat, make love, even commit suicide. Supervillains like Blofeld and the Joker owe much to Mabuse's Machiavellian madness: one henchman even gasses Wenk in his car!

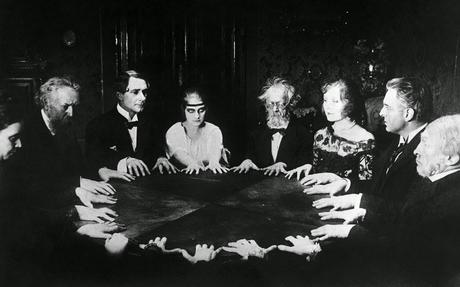

Mabuse's opening two hours are languorous. After the spectacular stock market opening, Lang settles into crafting his "Image of An Age" with nightclubs, seedy hotels, seance tables and smoke-filled rooms. Lang and writer Thea Von Harbou linger on settings while slowly introducing plot strands and supporting players: Wenk, Hull, the ditzy Countess and confused Count (Alfred Abel). The second half is brisker, tying its subplots and characters together for a satisfying conclusion.

Mabuse's opening two hours are languorous. After the spectacular stock market opening, Lang settles into crafting his "Image of An Age" with nightclubs, seedy hotels, seance tables and smoke-filled rooms. Lang and writer Thea Von Harbou linger on settings while slowly introducing plot strands and supporting players: Wenk, Hull, the ditzy Countess and confused Count (Alfred Abel). The second half is brisker, tying its subplots and characters together for a satisfying conclusion. Lang's direction overcomes the slow plotting. Otto Hunte creates weirdly stylized sets, including a retractable nightclub as intricate as Metropolis's future city. Even the respectable casino features flat triangle tables, cacti and wall masks. Lang and photographer Carl Hoffman experiment with surreal exposure effects: while Mabuse hypnotizes one victim, the background fades to black, leaving the Doctor's disembodied head. Or when the Count, and Mabuse, are menaced by ghosts, chairs morphing into monsters. There's little action, but the climactic siege plays as tensely as any modern thriller.

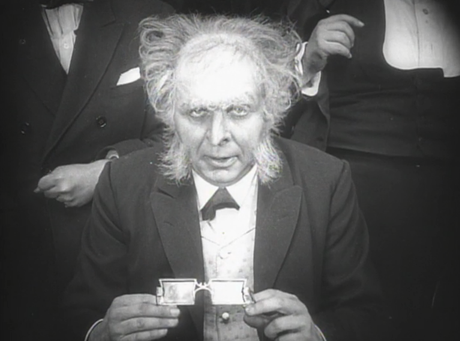

Rudolf Klein-Rogge had previously appeared in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and married Thea Von Harbou (who left him for Lang). Dr. Mabuse made Klein-Rogge a screen legend. He's an imposing presence, with coarse features, piercing eyes and perpetually arched brow belying his disguises. Hardly a subtle role, but Klein-Rogge relishes playing Mabuse's evil to the hilt. Naturally Klein-Rogge became typecast as villains, not least in Lang's Metropolis and Spies.

Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler is valuable as cinematic landmark, social document and entertainment. Lang revisited Mabuse in two sequels, and the character resurfaced in several lesser movies. While Testament is more accessible, Gambler is an indisputable classic.