Doc McStuffins, Disney’s black doctor character, is a “crossover hit.” Sales of Doc McStuffins character products are evenly distributed by race and even gender, prompting a popular refrain about the virtues of colorblindness, as reported by the New York Times:

Doc McStuffins, Disney’s black doctor character, is a “crossover hit.” Sales of Doc McStuffins character products are evenly distributed by race and even gender, prompting a popular refrain about the virtues of colorblindness, as reported by the New York Times:

“‘The kids who are of color see her as an African-American girl, and that’s really big for them,’ said Chris Nee, the creator of Doc McStuffins. ‘And I think a lot of other kids don’t see her color, and that’s wonderful as well.'”

If only that were true.

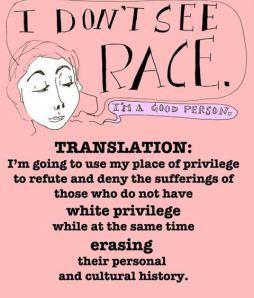

People want to believe that young children do not see color. It seemingly provides us with the opportunity to intervene on young minds before racial stereotypes take hold. If young children do not see color, then we can provide multi-cultural materials to promote diversity, even when our personal lives — where we live, the conversations in which we participate, with whom we educate our kids — fail to reflect the racial equality and diversity we say we value.

What is true is that kids do “see” color because it is embedded into the very fabric of who we are as a nation. But kids, especially white children, are taught to ignore what they see, which is very different than not seeing color at all.

In a sociology class I am teaching this summer for high schoolers who are predominantly white and upper-class, we started the course with them writing their “racial autobiography.” The exercise was meant to prime them for actively thinking and talking about race. Yet even though they were primed, their writing expressed a common, overarching theme: “You are not supposed to talk about race because you are not supposed to see race.”

Racial differences, inequities and segregation, for my students, were simply consequences of people wanting the best for themselves and their children. They believed that their ability to attend the best schools reflected their personal drive and the emphasis their parents placed on education. They believed that their admission into a very selective summer program was really only about their hard work. They believed that the fact that there were few black students in their high schools was nothing to be concerned about, for it was “just the way it is.”

But none of that meant they didn’t see race. For example, they understood what it meant to “act black;” they unanimously agreed that Justin Bieber “wants to be black” even though he’s “obviously white.” They agreed that I, a brown-skinned woman with locs, could never claim to be white just because I wanted to. “Why not?,” I asked. “Because you’re not.”

Oh. Okay.

Through explicitly talking about race, my students began to see that who they are and where they are is not race-neutral. They began to grapple with the fact that their highly resourced schools gave them an advantage in the Game of Life. They began to deal with the the fact of race, and that ignoring it made them feel better about themselves and their world. Not talking about race gave them a false sense of reality, but they do not want to be blissfully ignorant anymore. As one of my students said at the end of our first day, after discussing why race as we think of it (five to seven categories of easily identifiable groups) is a social construct and not justified through appeals to genetics, “Why have we never heard about this before?”

And that brings me back to Doc McStuffins. It is indeed a good thing that companies like Disney are using their vast market appeal to bring young children more diverse representations. I’m happy that Doc McStuffins is adding to the diversity of toys and games that all children can enjoy. But take my students’ experience as evidence: simply having diversity “in the air” is not enough. Leaving children to their own devices about issues like race and racism does not translate into lessons about equality, but rather presents the status quo as normal and as not in need of questioning.

We need to prompt our children to see and talk about race in order to be able to combat the pernicious effects of race. Doc McStuffins is a step. But she’s not nearly enough.