Creative Nonfiction by Melinda Gormley and Melissae Fellet

The White House, April 29, 1962

It had been pleasant weather in Washington DC all day. The air was still warm at 8:00 PM when Linus and Ava Helen Pauling arrived at the White House that evening. Ava Helen wore a floor-length cape over her formal dress, and white gloves covered her arms almost to the elbow. Pauling sported a traditional tuxedo.

Pauling and Ava Helen arrived just before the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, who had been the lead scientist of the Manhattan Project. Many heads turned toward the two controversial scientists as they waited in the receiving line to greet their hosts, the President and First Lady, John and Jacqueline Kennedy.

Pauling approached President Kennedy. They stood practically eye-to-eye.

“I’m pleased to see you,” the President said. “I understand you’ve been around the White House a couple of days already.”

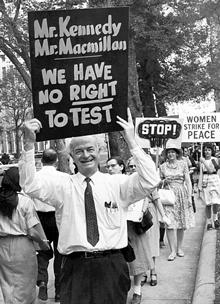

Pauling likely grinned and nodded, thinking back to earlier that day when he marched with other protesters in front of the White House, holding a sign that read “Mr. Kennedy, Mr. Macmillan, We Have No Right To Test!” Pauling, the 1954 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, had spent the better part of the past decade and a half as an outspoken activist for ending nuclear weapons testing.

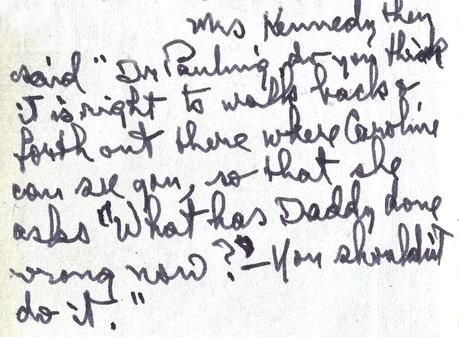

He shifted to greet the next person in the receiving line. Jacqueline’s pale mint silk evening gown and bouffant hair defined fashion. She flashed Pauling a large smile and extended her elegantly gloved hand. “Dr. Pauling, do you think it’s right to march back and forth out there where Caroline could see you?”

A hush fell over those nearby. Pauling didn’t quite know how to respond.

“She asked me, ‘Mummy, what has Daddy done wrong now?'” People nearby laughed and the tension broke. Clearly, Pauling’s message had reached the occupants of the White House, from the family’s patriarch to his young daughter.

Side-by-side for most of the evening, Ava Helen and Pauling, like all couples at this dinner honoring Nobel laureates, were seated at different tables for the meal. She approached her table to find she would be eating with many distinguished scientists, one of whom, Willard Libby, held opinions different from her husband and herself. She immediately decided to refrain from talking to him about politics and peace.

Ava Helen took her seat, and the historian and critic Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. sat down next to her, pulling his chair onto her chiffon skirt. It possibly occurred to her that this was going to be a long meal.

As they conversed, Ava Helen found Schlesinger to be antagonistic and unfriendly.

“Do you hold the same opinions as your husband?” he asked.

“I do for the most part,” Ava Helen responded. Last summer, she urged Jacqueline Kennedy, speaking mother-to-mother, to keep her children and the world’s children safe by pushing for a continuance of the moratorium on testing nuclear weapons.

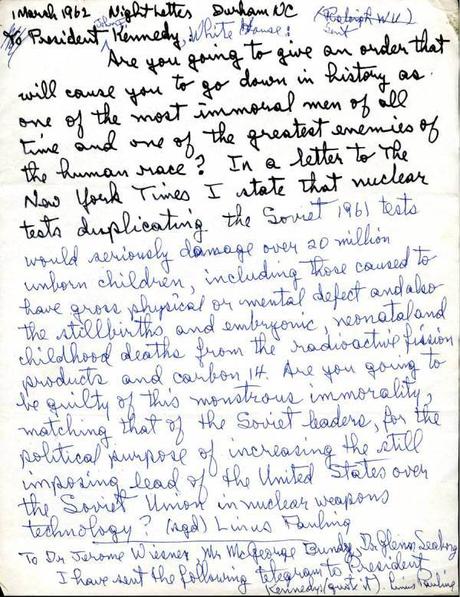

“Can I ask you a question?” Schlesinger asked. Without waiting for her response, he continued: “How can your husband accept an invitation to the White House after what he said to the President?” Schlesinger’s question referred to Pauling’s sharply-worded telegram, sent March 1, 1962, a little less than two months earlier.

In the telegram, Pauling asked the President, “Are you going to give an order that will cause you to go down in history as one of the most immoral men of all time and one of the greatest enemies of the human race?” Ire probably fumed from Pauling as he drafted the telegram. He couldn’t believe that President Kennedy was contemplating breaking his 1960 presidential campaign promises to not test nuclear weapons in the atmosphere.

Pauling’s note continued by referring to the Soviets’ detonation of several nuclear weapons in the atmosphere above Siberia. “In a letter to the New York Times, I state that nuclear tests duplicating the Soviet 1961 tests would seriously damage over 20 million unborn children, including those caused to have gross physical or mental defects and also the stillbirths and embryonic neonatal and childhood deaths from the radioactive fission products and carbon-14.”

Hoping to give President Kennedy some perspective about his decision, Pauling asked in his note, “Are you going to be guilty of this monstrous immorality matching that of the Soviet leaders for the political purpose of increasing the still imposing lead of the United States over the Soviet Union in nuclear technology?”

Throughout dinner, Ava Helen remained good-natured with Schlesinger. “There is nothing personal in either the invitation or the acceptance – Just the President of the U.S. having dinner with a Nobel Laureate.”

Looking tall, thin, and handsome in his tuxedo, Pauling likely approached her table after the meal ended, asking “How was your dinner?”

“Arthur Schlesinger is a clout and a boor!” Although she may not have told her husband this in this moment, she wrote down the exchange and her thoughts of Schlesinger after the evening ended.

Pauling would have smiled and thought to himself how lucky he was to have Ava Helen in his life. It was something he expressed aloud many times. He loved her for her pluckiness and devotion, among many other reasons.

The Air Force Strolling Strings played a lively Latin rhythm as the couple made their way after dinner across the main lobby to the East Room for three dramatic readings by the actor Fredric March. Rather than passing by the band, Pauling asked Ava Helen for a dance. Taking her into his arms he deftly guided her across the checkered floor. Her dark, short hair framed her face in waves and her chiffon dress whispered as she moved across the dance floor. Soon other guests joined them, setting aside political controversies for a little fun.

.