Pause for Effect

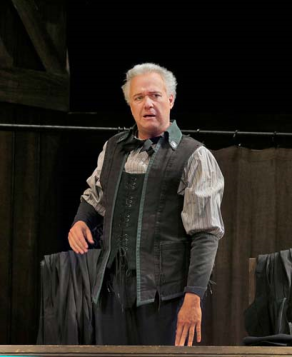

Michael Volle as Hans Sachs in Die Meistersinger (Ken Howard / Met Opera)

Michael Volle as Hans Sachs in Die Meistersinger (Ken Howard / Met Opera)

During the years 1857 to about 1869, Richard Wagner decided to take a break from his labors on The Ring of the Nibelung, a project that would occupy him for a good quarter century, by working on two unrelated subjects. It was Wagner’s idea that these works would be easier for opera companies to put on, thus guaranteeing him a steady income stream until the time was right for him to pick up The Ring’s threads.

The thought proved sound in theory, but nothing the Dresden-born composer attempted was as simple as all that. In reality, those “easier” subjects he had in mind turned out to be two of the most complicated and extraordinarily demanding works in the entire active repertoire. The first, a mythical tragedy called Tristan und Isolde (1865), was deemed by musicologists to be well-nigh impossible to perform in Wagner’s day, while the second, the massive comedy Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1868), would become his longest and most consistently accessible piece.

One must stand back and admire Wagner’s cheek (chutzpah is more like it) at imagining that either Tristan or Die Meistersinger would be within the grasp of European theaters of the time. What was Wagner thinking? Why, even in our own era one is bound to acknowledge that both these works, as staggering a compositional achievement as any, are vocally, if not technically, beyond the reach of many a modern-day opera house. Rare is the company that possesses singers of such skills and capabilities as those required to fill the needs of something like Die Meistersinger.

The Metropolitan Opera just so happens to be one of the few companies around where one can hear not only a reasonably decent performance of these stunning works, but on the Saturday matinee broadcast of December 13, 2014, listeners were greeted with a thoroughly satisfying, near exemplary transmission of the Met’s Wagner wing at its unrivaled best.

Having seen and heard Die Meistersinger on numerous occasions, I remain constantly amazed that such a volatile, boastful, argumentative, and thoroughly self-serving individual as Richard Wagner could write such a wondrously melodic, dramatically viable, and substantially artful masterpiece as this. It’s the only one of his mature works that doesn’t deal with such stage artifices as gods and goddesses, dwarfs and giants, heroes and dragons, knights and maidens, or plain old myths and legends.

Former record producer John Culshaw, in his book Wagner – The Man and His Music, made it clear that the single-minded composer had been “developing an aspect of his work that had emerged gradually” over time. “It was a question of musical and dramatic emphasis,” Culshaw continued, “and the relationship between the mystical and the real world.”

The principal characters in Meistersinger are, for the most part, based not on mystical but actual historical figures, or as close to “real world” personages as Wagner could create out of that enormously inventive mind-set of his. That the composer conceived this work as a comedy — a human comedy at that, with totally relatable characters and believable situations — makes it all the more astonishing in our eyes, considering how Wagner’s boorish nature constantly got in the way of his troubles.

Still, most opera lovers regard the cobbler-poet Hans Sachs as their favorite character, the one with the noblest of ideals and the most elevating of human qualities. My own predilection is for Sixtus Beckmesser, that nasty, ill-mannered town clerk and comic foil, as close to a doctrinaire Simon Cowell-type as can be invoked. This disagreeable fellow — in many ways similar in temperament to the dwarf Mime in Siegfried — was modeled on the Austrian writer Eduard Hanslick, one of Wagner’s harshest critics and a formalist at heart. Wagner originally intended to name Beckmesser after his fiercest foe, but thought the better of it not to.

The plot of Die Meistersinger, or The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, revolves around an American Idol-like song contest, ergo the comparison to Mr. Cowell. The prize of a hand in marriage to the daughter of one of the Masters serves as an added enticement to aspirants.

Incidentally, Wagner had previously composed an opera that took the song contest as one of its principal themes. That work, entitled Tannhäuser or the Song Contest at Wartburg, premiered in Dresden some twenty years earlier. Not exactly a hit with the public, Wagner tinkered with the score over the course of those same years. In 1861, Tannhäuser next became a cause célèbre at the Paris Opera when a drastically altered version was presented with (horror of horrors) a first act bacchanal. This thumbing of Wagner’s nose at Parisian “tradition” caused a near riot by the notoriously finicky Jockey Club, whose members demanded that their ballet be saved for Act Two, or else. Their ensuing disruptions forced Wagner to withdraw the work, a bitter blow to his easily-bruised ego and to his non-existent finances.

What relevance does all this have to Die Meistersinger? In hindsight, quite a lot, as did Wagner’s youthful dabbling in regional politics. For instance, the free-for-all street riot that closes Act Two of Die Meistersinger closely paralleled the Paris fracas and other unrests that Wagner had earlier participated in; and, at one point in his thought process, he had planned to present two back-to-back works — one tragic and one comic — involving song contests. Sandwiched in between both Tannhäuser and Die Meistersinger, however, were the mighty Ring cycle and the virtually unplayable Tristan. Wagner can be forgiven, then, for not having kept to his initial scheme.

At about the same time as Tannhäuser’s premiere, circa 1845, Wagner had formulated a scenario based on or around Hans Sachs and the Mastersingers, a well known and warmly regarded group of artisans. After his disappointment at the failure of Tristan to take hold (not entirely unpredicted, mind you, in view of that work’s complexities), Wagner plowed ahead with the composition of Die Meistersinger. He began by filling in a sketch he had started some sixteen years earlier. That was Wagner for you: always thinking ahead, no matter the cost.

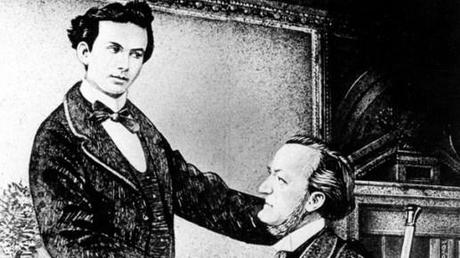

Without knowing it (or maybe he did, intuitively), Wagner also happened to be the luckiest artist alive. He soon met with his most loyal and passionately devoted supporter, the newly crowned King of Bavaria, the eighteen-year-old Ludwig II — one of many so-called Wagner fanatics, who was wildly enamored of Lohengrin and captivated by Tannhäuser, as well as more than willing and able to bankroll Wagner’s future endeavors to their fullest.

With his debts absolved and paid for, and his financial obligations apparently taken care of by his young benefactor, Richard Wagner was in the enviable position of wrapping himself full-time in his words and music — and in extravagant silks and elegant furs, all at Ludwig’s expense.

Musically Satisfying

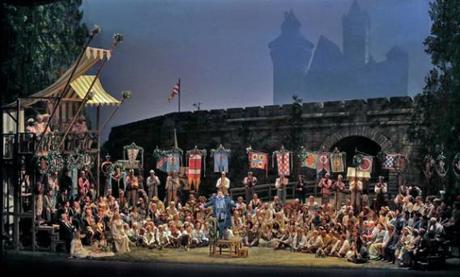

The roar of greeting and approval that James Levine received before every curtain spoke volumes for how much New York audiences have missed the presence on the podium of their musical director. Before the formidable Met Opera forces (unequalled in this piece, I’ll have you know), Maestro Levine led an extraordinarily shaped performance, as did Chorus Master Donald Palumbo.

After the Act III prelude, a mournful, melancholy piece, Levine never languished. Both cello and double basses were full and soothing, yet never booming or intrusive. The maestro lingered over details, especially in his clarity of tone and the singling out of individual instruments: for example, the oboe at the Act I curtain, the bassoon at the close of Act II, and the muffled horns at the start of Act III — even the gorgeous strings in Sachs’ “Wahn” monolog — all beautifully tailored to the scenes at hand. Levine imposed his will on the chaotic comings-and-goings of Act II — not an easy thing to do in the anarchy that concludes that act.

The orchestra maintained the right coloration throughout that seemingly interminable third act. In scene two of that act, the robust “Dance of the Apprentices” was most welcome for its sprightliness and unremitting joy. Indeed, this was one of Maestro Levine’s finest hours, an early Christmas present to his fans and to listeners worldwide. In Levine’s hands, the opera flew by in record time. That’s about the best compliment anyone can give concerning Wagner’s longest opera, and for that Maestro Levine wins the prize!

The mighty Met chorus was stupendous in their gloriously inflected delivery of “Wacht auf!” (“Awake!”), the Nuremberg citizen’s greeting to their beloved city and their cobbler-poet Sachs — so like a Bach chorale in its counterpoint and harmony. The orchestra and chorus took home the honors as well.

Michael Volle, the Hans Sachs, was more baritone than bass. His is not a large voice, but it carries well without the wobbles or strain of past Sachs (I’m thinking of the Bavarian State Opera’s recording with Otto Wiener as an excruciatingly over-the-hill cobbler-poet). For the record, Volle scored a major triumph at the Met (at least, as I heard it on the radio). The role of Sachs is a gargantuan undertaking by any measure! The sheer quantity of words and music is beyond belief; added to these, the requisite acting of the highest order, and the goal becomes almost unattainable.

Impossible, you say? Probably — even more so when one is bereft of the visual component, another key element in singing this part. What I heard on the Saturday broadcast was more than acceptable. I did miss some of the sturdiness of tone below the staff or the rock-solid solidity of Sachs’ lowest notes, none of which were within Volle’s reach. What I did discern was a leaner than normal Sachs, leaner but not meaner. The character’s warmth and world-weary wisdom came through loud and clear, especially in the grueling two-hour third act, a mammoth vocal and verbal outpouring that singers more massively endowed than Volle have had greater difficulty with.

This is without argument Wagner’s most humane work, and Volle finished up stronger and less tired on this occasion than any of his recent predecessors. I have nothing but the highest praise for his efforts and his successful closing paean to German art — movingly and brilliantly sung.

As Beckmesser, baritone Johannes Martin Kränzle has a voice similar to that of Hermann Prey, who sang the role at Bayreuth in the 1980s. He has an interesting but not too perturbing vibrato, a good command of style and feel for the text. His coloratura wasn’t all that smooth, but then again attractive scales and passagework are not the point of this part; rather, a strong flair for showy comedy and exaggeration works wonders over the long haul. This Kränzle had in abundance, along with a flexible voice and timbre. His confrontations with Volle’s roguish Hans Sachs were the highpoints of the afternoon (a long one, by my reckoning).

As Walter von Stolzing, the young knight who woos the beautiful Eva Pogner, South African tenor Johan Botha easily surpassed expectations in this character’s music, with strong high notes, a sturdy middle voice, and a poetic streak with the all-important text — all significant attributes of this extremely wordy part. A steady outpouring and a good pair of lungs, along with fearless stabs at the Prize Song’s unremitting tessitura, earned Botha the cheers of the crowd. This was miles and away his best role to date at the Met. The mere fact that he sounded better at the end than at the beginning was noteworthy in itself.

The gigantic toned Hans-Peter König’s rich-voiced Pogner was almost too powerful. He easily overcame most of the hurdles in his Act I address to the Masters. The equally high range of this part held no terrors for the German bass, a blessing in a role that has too often been taken by lesser mortals that lacked the necessary top extension. In this, König was “king” (pun intended).

Beauty in Bel Canto

No finer David exists in my experience than tenor David Appleby, heard previously at the Met primarily in Mozart and Gluck. He demonstrated an ample tone and purity of vocalism that only the best bel canto singers can achieve.

Indeed, his background in that department and facility with note values outweighed any shortcomings associated with past exponents of this frequently under-cast assignment. Add to that some clarion top notes and we might one day be witnesses to a formidable Mime in our midst. In sum, it was a real pleasure for once to hear David sung so well, where previous singers have labored through the apprentice’s lengthy, drawn-out description of the various master tones; here, Appleby made the whole of his Act I “sermon” a joy to listen to. Keep up the good work, David!

Eva’s music was well taken by Annette Dasch, a spritely and lively yet feminine Fraulein with enough spunk in her makeup to make any man fall desperately in love with her. The only thing missing in her performance was that spark of springtime in the voice. Dasch was slightly monochromatic and could have explored the character’s development from girlish playfulness to womanly wiles more fully. Her clever ingenuity and sense of competiveness with Sachs, for example, felt timid and unsure where it should be forceful and forthright. A little unsteadiness in the highest reaches marred an otherwise pleasurable assumption.

Praise must also be mentioned for the Night Watchman of British basso Matthew Rose, mellow toned and wistful, although he drifted from the pitch at times. His comic antics pleased the audience to no end. Rose got a solo bow at the end of Act II, a nice touch on the Met’s part.

Die Meistersinger is many musical motifs removed from the world of The Ring or its companion piece, Tristan und Isolde. Yet the ghost of both the Ring and Tristan remain ever present, in the first scene of Act III and in many of Sachs’ midsummer reveries during Act II.

With these in mind, the acid test of any Meistersinger production is the Act III quintet. The lead up to it was expertly articulated by Volle, clearly comfortable with his native German and the style of the music. Maestro Levine took the number in a leisurely but not too lugubrious pace. Soprano Dasch began, softly and assuredly, with Botha firmly joining in and Appleby applying just enough voice to stand out from the rest. The same goes for Volle, who followed as well as he could the vocal lines of the other participants. It ended quietly and dreamily, one of the better quintets I’ve heard in a long time of opera-going.

Rounding out the cast were Karen Cargill as Magdalene, Martin Gantner as Kothner, and Benjamin Bliss as Vogelgesang, all contributing to the success of the afternoon. The biggest news was that Michael Volle survived this marathon assignment with voice and honor intact, and without sounding too frayed on top, or too tired by the end — a major accomplishment that hints toward a future traversal as Wotan and the Wanderer in the Met’s patented hi-tech Ring cycle.

Copyright © 2015 by Josmar F. Lopes