The Count (Bela Lugosi) welcomes Renfield to his castle in Dracula (1931)

The Count (Bela Lugosi) welcomes Renfield to his castle in Dracula (1931)The Fear Factor

Like many individuals of my generation before and after me, I grew up with movie monsters. Horrifyingly repulsive creatures (or so I thought), as well as fantastically winged dragons and unidentified flying objects — all of them, thank goodness, brought to our family’s living room courtesy of the medium of television.

Since I wasn’t given much of a spending allowance to go to the local cinema, I was forced to gratify my precocious urges for the bizarre and the unconventional, not to mention those elaborate special effects, through old movies and first-run TV shows.

Credit for keeping my probing eyes under the bed covers was due to such local programming as Million Dollar Movie, Creature Features, and The 4:30 Movie. They provided sufficient grist for my movie-mania mill. These and other programs, i.e., The Late Show, The Outer Limits, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Lost in Space, Land of the Giants, The Twilight Zone, and The Time Tunnel, kept my natural curiosity about the supposedly grotesque world around me at full tilt.

My older cousin and his friends, knowing of my fascination with movie monsters (and my equal fear and loathing of said beasties), had the nasty habit of flashing monster playing cards at me — one more outrageous and disturbing than the other. They would get a tremendous kick out of my revulsion at the black-and-white photographs of despicable demons, eerie human skulls, and maniacally cackling witches. ARGH!!!!

Not satisfied with that, I remember pleading with my mother to buy those outlandish Aurora Monster Model kits, where, in the safety and comfort of our apartment I could exorcise those personal demons by creating my own fleet of sinister fiends.

As I matured, I realized these photographs and model kits were nothing more than mere advertisements; that “reel” monsters and their ilk were not “real” after all, only figments of some eccentric filmmaker’s wild-eyed imagination. Only then did I realize that horror was rooted in the psyche — a psychological explanation for the unrealized fears buried deep inside our subconscious thoughts.

There was no logical rationalization for these thoughts. Consequently, therein lay the reason why we feared them: one, as a projection of real-life objects or issues; and two, as the cause for these fears. If we could confront and conquer our fears, the theory is they will be removed (or so they say).

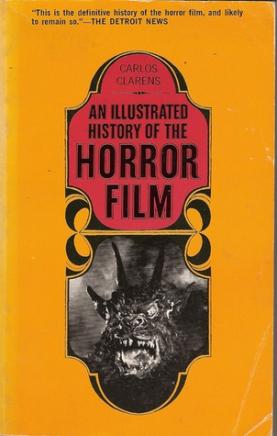

Years later, while still in high school, and not long after that, I came across one of the qualified classics of the academic genre, Carlos Clarens’ An Illustrated History of the Horror Film, a superbly written survey of movies from the late nineteenth century up to the mid-1960s (the so-called “classic” period) covering this same aspect. It was this very book, with its concisely edited and elaborately conveyed text, that finally brought me out of the darkened room of my qualms and into the light of discovery.

Clarens’ cogent yet discerning text convinced me that horror, fantasy, and science fiction were a viable art form, to be studied and admired. The genre could be tailored and shaped to aptness and precision by a talented team of dedicated artisans and supremely skilled craftsmen of the highest order.

With this newly-acquired awareness in hand, I set out with a slight degree of unease — a holdover from my youthful trepidations, I suppose — to venture forth where no film buff had gone before: that is, to revisit as many of the films that had once fueled my dreams and nightmares, and face my childhood fears. The experience of watching these vintage motion pictures with a fresh outlook and perspective, and in an entirely new light (sorry, Count!), was one I had long wished to share with likeminded readers.

Though not necessarily in strict chronological order, I have modified this list to contain films that have exuded a profound influence and sway on me personally. There is no conceivable way this list can be as all-inclusive as I would like, or encompass the full range of cinematic possibilities that are available to film buffs.

Therefore, with that caveat in mind please accept my apologies beforehand to those films that could not be reviewed.

Bites and Howls

One of the most popular and trendiest of the many horror-movie categories that have captivated viewers, and the one with the longest so-called “lifespan” (vide the Twilight, Blade, and Harry Potter series, to mention only a few), is the vampire and werewolf genre.

The first documented mention of vampirism in literature came from writer and physician John Polidori’s work of fictional prose, The Vampyre, published in 1819. This lurid tale’s protagonists concentrated on a mysterious Lord Ruthven, a minor aristocrat of dubious ancestry (modeled after the poet Lord Byron), and his traveling companion Aubrey, based on the author himself. As the story progresses, it is revealed that Ruthven was one of the undead: a ruthless creature with an unquenchable thirst for human blood.

This was one of several yarns to have emerged from the vivid imaginations of a June 1816 gathering at Villa Diodati, a mansion off Lake Geneva in Switzerland. It was here that Byron and Polidori, along with English romantic poet Percy Shelley and his betrothed, the eighteen-year-old Mary Wolstonecraft Godwin (soon to be Shelley), reputedly passed the time by reading ghost stories and telling one another fantastical tales of the unnatural.

Among the stories spun over a three-night-period were the rudiments of Mary Shelley’s classic science-fiction/horror novel, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus (1818), a work that itself has fueled countless permutations and movie spinoffs.

From this beginning, other vampire potboilers began to circulate, including the serialized “penny dreadful” Varney the Vampire, or the Feast of Blood by James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest (1845-47); and especially Irish author Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (published in serial form in 1871-72), about a lusty female vampire who preys on “lonely young women” that also served as inspiration for a fellow Irishman, the Dublin-born theater manager, writer and lawyer Bram Stoker.

Told in a combination of letters, journals, diaries, newspaper articles, ships’ logs, and individual accounts, the Gothic novel Dracula (1897), while not an immediate sensation, nevertheless met with critical favor. The book eventually took off just as the advent of silent cinema came into being.

Stirred by the success of Stoker’s Dracula, German-born film director Friedrich Wilhelm (F.W.) Murnau decided, in 1922, to make Nosferatu (“The Undead”). This first recorded vampire flick has stood the test of time as an undisputed masterpiece of peculiar, horrifically bone-chilling sequences; a veritable symphony of scary movements filmed in naturalistic surroundings near the German port city of Wismar. Since the original title happened to have been Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (“A Symphony of Horrors”), this description is more than apt.

Some may find the movie silly or quaint, or even old-fashioned and out of style, but seen in its proper element — i.e., on a large screen and in a darkened movie theater — the picture’s ability to shock and provoke audience reaction is still very much alive. Although Murnau failed to secure the rights to Stoker’s book (the author’s widow sued him for copyright infringement), he was still able to transmit the key ingredients to the silver screen that made the figure of Count Dracula so menacing. This remains a work of mesmerizing potency.

Renamed Count Orlock and played by German actor Max Schreck (whose surname in English means “fear”), that repulsive rat-shaped head, those gloomy sunken eyes and claw-like appendages that served as fingernails (sometimes seen in shadowy silhouette) pummeled early movie audiences into frightened submission.

The style of the film has been described as expressionistic, which isn’t entirely accurate since the term itself is supposed to eschew realism in favor of a projection of intense inner emotions or feelings. Still, that look of unvarnished evil, accelerated time-lapsed cinematography, and that final image of Orlock slowly fading away to nothingness as the sun rises will remain in viewers’ minds for a long time to come.

There was nothing inherently sexy about this beast, of that we are certain, even though the object of his bloodlust, Nina (a variant on Stoker’s Minna Harker), a pure and “virtuous woman,” sacrifices herself to this monster in order to destroy him.

Call Me Dracula

When Universal Pictures finally decided to film the sound version of Dracula in 1930 (itself based on a successful Broadway theater adaptation by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston), the studio contracted with director Tod Browning to assume the project (after their first choice, German filmmaker Paul Leni, had died). It was also rumored at the time that famed silent horror-movie alumnus Lon Chaney would be tapped to star as the lead, which made sense from a practical standpoint.

Chaney and Browning had previously worked together on a variety of features, including such macabre outings as The Unholy Three (1925), The Unknown (1927) with Joan Crawford, and the long-lost London after Midnight (1927), Browning’s initial attempt at a hybrid vampire-cum-murder mystery. Incidentally, the film was remade by MGM in 1935 as a talkie and re-titled Mark of the Vampire. Headlined by Lionel Barrymore, it co-starred a heavily-accented Hungarian stage and film veteran named Bela Lugosi.

With Chaney’s unexpected passing to cancer in August 1930, the way was cleared for other actors to assume the mantle of Universal’s king of horror. After the Broadway run of Dracula, the play went on tour with its principal performer intact. Bela Lugosi, whose real name was Béla Blaskó, just happened to have been born in the city of Lugos, not far from the same rural Transylvanian district and Carpathian mountain range as the bloodthirsty Count (how’s that for a coincidence?).

After two years on the road, Bela decided to put down stakes (no pun intended) in California where he started appearing in early silent and sound productions. Lugosi even co-starred in a Tod Browning picture, The Thirteenth Chair (1929), with Conrad Nagel and Leslie Hyams, which may have kept him in the director’s mind once Dracula came around.

I can’t tell you what made this early sound venture so shocking to audiences of the time, except to say that it grabbed startled viewers from the start. To our modern-day sensibilities, Dracula seems hopelessly stilted and outdated, especially in its stagier second half. Released in February 1931, it’s a labored, slow-moving effort, ponderous in spots and overly talkative, with some of the acting clearly belonging to the theater.

Despite these lulls, the film comes “alive” (so to speak) anytime the formidable figure of Count Dracula is on the prowl, quite different from that of his predecessor, Max Schreck. Bela’s darkly sinister mien, unblinking stare, and imposing aristocratic bearing and height (he stood six feet and one inch tall) were his most prominent features. And contrary to what most producers might have imagined, his thick, deliberately-paced Hungarian accent was an added bonus in defining the character’s “other-worldliness.”

One of my favorite scenes is the clash of wills between Dracula and Professor Van Helsing (woodenly but sternly played by character actor Edward Van Sloan). As the two arch-enemies glare at each other in defiance, Dracula breaks the silence with the enigmatic words, “Your vill is strong, Van—Hel—zing!”

Another memorable episode occurs early on in Castle Dracula, where the Count greets the unsuspecting Mr. Renfield (played by the pop-eyed Dwight Frye): “I—am—Drac-ula,” Lugosi pronounces. “I bid you—welcome.”

Then, as they slowly mount the massive staircase, the howling of wolves interrupts their upward motion.

“Listen to them. Children of the night!” Dracula’s voice cracks momentarily. “What mu—sic they make!” As Dracula reaches the top of the stairs, he walks straight through the cobwebs — without disturbing them in the least! Talk about creepy; this sequence will chill you to the bone.

Other scenes involving Dracula’s stalking of his female victims were said to have driven ladies in the movie theater to distraction. This brings up a question I’ve always wanted to ask: What made Dracula so attractive to women?

Writer James V. Hart, who was responsible for the screenplay to Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film adaptation Bram Stoker’s Dracula, found that one scene in Stoker’s book was so “intensely erotic and diabolically evil that I passed out right in my foie gras … Eventually, I caught up with … the Bela Lugosi standard that caused people to faint in the aisles.” Hart was “also impressed with Frank Langella’s interpretation on Broadway, which brought a sexual energy to the character never before seen.”

In addition to which, Hart insisted that “Women more than men have tended to read Dracula and other vampire stories, and to understand the vampire’s attraction. Vampires,” he went on, “offer a delectable alternative to the drudgery of mortal life and the promises of religion.”

Artist, animator, and film director Tim Burton may have gotten it right when the late Martin Landau, in his Oscar-winning performance as the older Lugosi in Ed Wood (1994), voiced a casual aside to maverick eager-beaver filmmaker Eddie (Johnny Depp). As the two walk up to his broken-down apartment, Lugosi makes the following observation:

“The women … the women preferred the traditional monsters. The pure horror, it both repels, and attracts them, because in their collective unconsciousness, they have the agony of childbirth. The blood. The blood is the horror” (Ed Wood, from the screenplay by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski).

This may have been nothing more than armchair analysis, but it nonetheless helped to explain the vampire’s enduring legacy and popularity.

The excellent camera work in Dracula was provided by Bohemian-born émigré Karl Freund, who was Fritz Lang’s principal photographer on the science-fiction screen epic Metropolis (1927) and who also went on to direct several stylish productions of his own, including Universal’s The Mummy (1932) with Boris Karloff, and MGM’s Mad Love, aka The Hands of Orlac (1935), with Peter Lorre, as well as numerous episodes of I Love Lucy in the 1950s.

The misty atmosphere in Dracula no doubt heightened the Gothic mood, at least in the film’s first half. As far as we are concerned, the only thing missing was a decent music score. Unfortunately, the opening snippet, derived from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake ballet, along with wisps of the Overture to Wagner’s Die Meistersinger and Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony are about all we get.

(To be continued…)

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes

Advertisements