Je suis Charlie Hebdo, et aussi Michel Brown, et aussi Darren Wilson et aussi…

As Teresa Prados-Torreira recently observed in this space, the last month has seen an international slurry of reactions to the Charlie Hebdo Massacre from outraged officials, scampering journalists, erstwhile academics, dedicated peace-keepers, and, of course, the international community of artists, cartoonists, and satirists.

Prados-Torreria astutely summarizes in her 20 January post, “at first glance, it seems obvious that the answer to this dilemma should be a wholehearted affirmation of the need to stand in solidarity with the French magazine, with the murdered cartoonists, and in support of free speech. But the content of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons, their irreverent depiction of Mohammed and Muslims, have resulted in a cascade of critical essays online and elsewhere.” Many have since noted that, for interpreters within and beyond French culture, the magazine’s scabrous treatment of all things sacred and sanctified could be labelled either courageous or irresponsible depending upon personal preference. One thing is certain, though, Charlie Hebdo was rarely, if ever, about discretion. Even more interestingly, a new angle on the extensive media coverage of the attacks has taken shape that inquires as to why the tragic murder of several talented artists has become, either incidentally or on purpose, a larger global issue and a much more public and popular rallying point than the rampant cruelties taking place in Nigeria involving Bok0 Haram? Even more interestingly, we have to admit that slander, satire, and ridicule of Arabs, Muslims, and Islam are hardly rare in America mainstream culture. Consider the skirmishes that erupted over the years surrounding Johnny Hart’s abuse of Islamic and Judaic symbols in several episodes of his comic strip, B.C., especially the “potty humor” episode that fused the sacred icons of Islam with the half-moon of an outhouse door. Is this not Charlie Hebdo territory?

With the rhetorical avalanche surrounding Charlie Hebdo just beginning to settle, we might wonder if any more discussion could possibly serve to alleviate the tension, fear, and uncertainty that has seemingly spread across our righteously outraged global public. It’s a very fair question, but instead, I would like use the terror attacks in France, and their subsequent influence, to explore a few more local and personal concerns about the deploying of satire, the power of cartoons, and the often unexpected inaccuracies of visual wit.

Since the assault on the Charlie Hebdo offices, there have been several inspiring statements of solidarity and strength in support of free speech and equal opportunity insult, most notably including the great public demonstrations in Paris, throughout France, and across the world.

Can there ever be a more heartening and honest sign that humor – especially in its most relentless, hostile form – deserves our attention, respect, and scrutiny?

There have also been a wide variety of high profile reactions and commentaries throughout the intellectual honeycomb of bloggers, critics, and scholars. Much has been made of Joe Sacco’s somewhat disappointing Guardian catechism “On Satire.” Important statements have also arisen from doyens of provocative comics including Art Spiegelman, Keith Knight (who produced two suitably irreverent texts from very different perspectives), and Steve Benson, among many, many others. Scholars also, have contributed valuable and sometimes revelatory insight into the complex legacy of French cartooning and its contribution to both Charlie Hebdo’s editorial policies and the violent reactions that it frequently instigated. Bart Beaty and Mark McKinney have offered reasoned and informative assessments that went largely ignored in the media frenzy following the attacks.Even richer and more comprehensive studies of the violent potential of editorial cartooning have also arisen from astute historians like Paul Tumey and Jeffrey Trexler.

Cartoonists, of course, have been at the vanguard of the fight for freedom of speech, recognition, and reaction. From the very moment that news of the attack broke in France, powerful responses like this one were quickly finding their way around the world’s webs.

The translation is simply .”The ducks will always fly higher than the guns.” This seems a fitting commentary on everyone’s natural right to free speech, peaceful tolerance, and artistic expression but for the French reader, as I have come to understand it, the cartoon also includes sly references to the enduring poignancy of journalism and the relative pointlessness of murder, terror, censorship, and repression. As far as I know, this cartoon comes from the first wave of responses to the assault on the Charlie Hebdo offices.

In America and across the globe, multiple strains of pro-Charlie cartoons, caricatures, and sketches have arisen, many of which are even more vehement, moving, and shrewd than the works which originally inspired the killings themselves. Of the many responses, prose and picture, professional and amateur, poignant and perverse, I have been most encouraged by the collective voices of Arab cartoonists, who, like so many others, dedicate their lives and their art to pointing out hypocrisy, corruption, and privilege at considerable risk to their own health and safety. Perusing this particular collection of drawings, loaded with invincible pencils, futile bullets, buffoonish terrorists, and martyred soothsayers speaks honestly and powerfully of the compulsion towards dissent and ridicule that all satirists and slanderers embody.

I recall an incredible lunch conversation I once shared with Paul Levitz, Editor-in-Chief Emeritus at DC Comics, who described his fascinating meeting with a group of Arab cartoonists on a goodwill cultural exchange to the US. Among other mainstays of the American landscape like the Statue of Liberty and the Smithsonian, they were especially eager to visit Mad Magazine headquarters, and, as Levitz recalled to several companions at the 2011 OSU Festival of Comic Arts, they desperately wanted to know how such incredible satire could be published so freely without governmental interference or public scorn.

Paul Levitz, one time Editor in Chief of DC Comics, with the star-struck author, after discussing his insightful meeting with Arab cartoonists at the 2011 OSU Festival of Comic Arts.

As Charlie Hebdo has since revealed, these visiting humorists from less tolerant cultures and more hostile regimes, were quite familiar with a kind of danger that many artists, journalists, and humorists have long forgotten. Protest, provocation, and dissent are always risky playgrounds, especially when they amplify already tumultuous debates surrounding ethnicity, gender, and belief.

The free, tee-shirt wearing world has seemingly united around the Charlie Hebdo incident and the lessons it tries to teach us about art, terror, and hate. Yet, whether or not we find Charlie Hebdo‘s vehement slaughter of all sacred cows important, inane, innovative, or irresponsible, the derogatory power of cartooning brings many different concerns into sharp relief. Terrorists, are of course, eventually going to kill somebody or destroy something. They are, after all, looking for reasons to activate their agendas and force us all to recognize their vital role they play in whatever holy crusade, ethnic grudge, or extremist stance they might righteously and violently represent. Our best defense, then, would seem to fall along the lines of a more informed, compassionate, and internationalized public that strives to understand each other more sincerely, wisely, and peacefully. As we all know, humor, comedy, and satire can play enormously important roles in that process. OR, they can muck it up good!

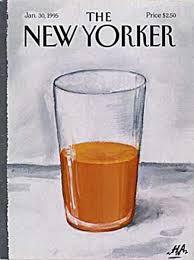

For years, I have taught my students about close critical analysis using one of my favorite venues for witty cultural commentary: the astutely satiric cover imagery of The New Yorker. Relying on a wide variety of artists, themes, and subjects, The New Yorker‘s cover is as common a sounding board for the American Liberal Arts as NPR, PBS, or the recently deceased Roger Ebert. For more than a decade, I introduced students to the multiplicity of meanings inherent in complex texts by discussing the uncertainty and ambivalence of Ha’s New Yorker commentary on the OJ Simpson trial.

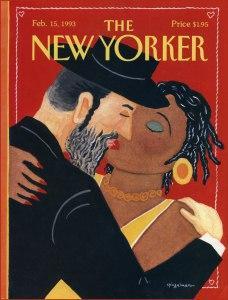

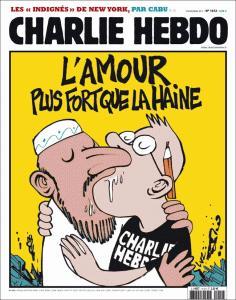

After many years, I moved on to more obvious and current, but equally controversial covers like the infamous Valentine’s Day interracial Rabbi’s kiss by Art Spiegelman. Interestingly, this calculated statement about the barrier-bashing power of romantic attraction seems to pair well with what is arguably Charlie Hebdo‘s “most famous” cover depicting a Gay French kiss between a traditionalist Muslim and a Caucasian cartoonist.

Although Charlie Hebdo will never be the Parisian equivalent of The New Yorker, the satiric address of both covers works along the same lines. At best, both designs ask, “Why get hung up on limits and restrictions? Love is love.” They both challenge us to ask, “Are we strong enough to accept this?” I find it very easy to align my own ideas about freedom, fairness, and relationships with Spiegelman’s famous interracial couple. They blend diversity of race, faith, gender, and perhaps also age with a fun and positive sense of provocative delight. In the same vein,the homosexual embrace on the Hebdo cover functions like an extreme litmus test to prove that, as the caption claims, “Love is stronger than hate,” even when it is drenched in man-drool! In both cases, humor and shock stick it to anyone too strict, prudish, or or bitterly presumptuous about other people’s behaviors. We, hopefully, can look at both images and laugh at each other with equal candor.

That is not so true with the next image I would like to discuss. Again, the covers of The New Yorker have been providing me with convenient, topical teaching material for decades and I have never shirked from allowing my students to explore their own ethics and perspectives in interpreting their plethora of codes of meanings.

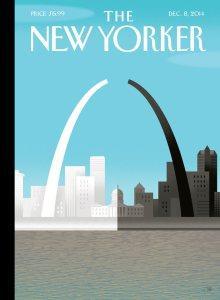

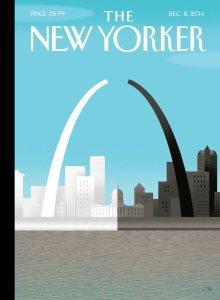

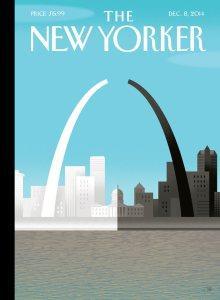

All of that became much more difficult on December 8, 2014 when the magazine published Bob Staake’s image in response to the recent conflicts in Ferguson, MO.

I have taught Humanities, Humor, and Writing courses in St Louis since the Fall 2007. While not native to the city, my family and I have learned to embrace its uniquely “Haute Hoosier” or “Hoosgeois ” Midwestern blend of baseball, beer, and belly laughs. For more on the uniquely humble “hoosier” culture of St Louis, check out this handy, hilarious guide to surviving the odd quirks and peculiar lingo that define the Gateway City. In our several years living in the heart of St Louis’ diverse and vibrant South City neighborhoods, we have also learned that Race in St Louis and its variety of outlying communities is not quite like anywhere else in America. Though, not surprisingly, it is not all what the news media would like you to believe.

There are, of course, prosperous predominantly Caucasian suburbs like Clayton, Chesterfield, Webster Groves, and Ladue, as well as an assortment of famously smoldering ghettos like East St Louis, North City, and now, supposedly, Ferguson. Then, there are uniquely internationalized quadrants and corners where Bosnians, Eritreans, Vietnamese, Ukrainians, and other immigrant groups have settled with great success. St Louis is also home to one of the most industrious, creative, and uncompromising African American communities in the nation. Producing visionaries like Katherine Dunham, Josephine Baker, Redd Foxx, Reginald Hudlin, and a wide range of equally influential innovators and provocateurs, Blackness in St Louis has always seemed to own and sharpen the chip it carries on its very strong, proud shoulder. Only in St Louis have I seen students question the legitimate “blackness” of senior African American faculty. Only in St Louis have I ever had African American students joyfully tell me that the most important thing they learned in my class was that “not all white men are assholes,” and only in St Louis, have I ever been applauded spontaneously by African American students for refusing to utter the “N-word” when discussing or reciting from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

More importantly, only in St Louis have I ever seen the pain and fury and violence of the ghetto so very close to everyone’s lives. I have lived safely and comfortably in some of the supposedly “most dangerous” cities and neighborhoods in the world and I never had a student come up to me during class to apologize for not finishing his essay on time because he was stabbed through the hand, all while still trailing blood through a saturated towel, until I came to St Louis. I have sadly had several students lose children while they were taking my classes, but I never had a student call me from the ER while their child was dying to explain the situation until I came to St Louis. I have always let my students “teach me” their world through trends in slang, fashion, and music, but I never had a student confidently and happily teach me their old signature gang gestures until I came to St Louis.

In other words, we are clearly a city like many others, littered with conflicts and crimes relating to class, race, and aching aching need. What we are not, however, in any way at all is divided into the flat and static binary of segregated black and white that The New Yorker‘s “Broken Arch” cover so smugly applies to a terrible situation. Our city’s intense dysfunction, like our nation’s, goes well beyond simple definitions of “black and white” identity or even Black and White humor for that matter. It just isn’t accurate or insightful or even insulting. It is, rather, a simple cheap shot at the exposed soft tissue of our culture’s most important and volatile fault line. Humor is a tool for expanding such awareness, understanding, and change, but this “witty” image seems nowhere near as effective and defensible as the most abusive and grotesque of Charlie Hebdo’s assaults on religion.

Race in St Louis and Ferguson and everywhere else in the vicinity is different because it is always more intimate, more constant, and raw. Our problems do not arise from the separation and isolation of Black and White. There is no missing linkage at the top of our arch. On the contrary, it is the intensity and extremity within the points of connection themselves – and our relative disappointment in the failure of those bridges to mutual acceptance and togetherness in the case of the Michael Brown shooting – that makes St Louis worth caring about and, more sardonically, worth satirizing. Our arch is not broken. It is overburdened.

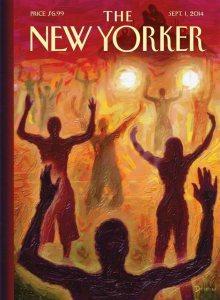

It’s not that I am so hypocritical that I cannot accept deep and biting satire of my own communities. Far from it. The killing of Michael Brown was an outrage for the African American community, the law enforcement profession, and every other population our city nurtures. That is equally true for the many brave protestors and responsible peacekeepers who found their own neighbors and friends turn against them in the days following the shooting, looting, and rioting. For my part in the fracas, I gladly shared the New Yorker‘s September 1st protest cover by Eric Drooker, another noted graphic novelist, with students, friends, and colleagues. It went a long way in helping us all develop a safe and comfortable forum for voicing anger, fear, and confusion over the shooting, the riots, and the media swarm that followed. Much of our efforts at coping involved the need to laugh together. For all of these reasons and more, my students loved Eric Drooker’s cover as well as the tough true discussions that arise around it. Though I have only been able to work with the “Broken Arch” in a few classes early in Spring semester, the reaction is simply not the same. Instead of discussion and debate, it seems to inspire resentment and disappointment.

In Drooker’s image, my students find real human hope for change. It is all bodies, motion, and community. It is in fact, well aligned with a city seeking resolutions and a world that is watching with great hope. Staake’s design, however, is a depopulated anti-postcard that makes calculated use of our most famous tourist trap as well as the old Courthouse, equally famous for its role in American racial history, as the site of the Dred Scott trial. Were either the artist or The New Yorker even aware that, along with a desecrated arch, they were also bifurcating an enduring symbol of the individual African American’s historical struggle for liberty and independence? In Scott’s case, the clinical division of black and white seems somewhat more appropriate and (ahem) cutting, than it does for the tragic death of Michael Brown.

Finally, we are left with one more intriguing irony involving buildings, killings, covers, and drawings.

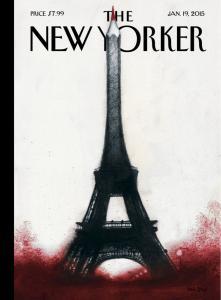

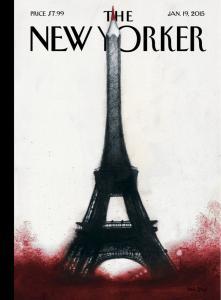

The New Yorker‘s January 19, 2015 cover displays a stunning, post-Charlie Hebdo celebration of the enduring spirit of Parisian art, French democracy, and Gaellic pride as depicted in Ana Juan’s incredibly moving, “Solidarite.” The design is an incredible statement of strength and beauty, and a potent testament to the power of uncompromising art. Francoise Mouly, among the most important supporters of cutting edge cartooning and innovative humor in the last half century, finds it especially sensitive to the feelings and needs of the people and communities it symbolizes.

Once again, a single icon stands for a city in mourning. Another act of violence is supposedly overcome or honored or eulogized or mythologized with a cover design of cartoonish origins. This time, however, the message is one of wholeness, integrity, potential, and promise. The healing that seems so lacking in our un-mendable Arch seems very real and immediate here. The carnage, rage, and hate cannot blot out the triumphant lines of one of the world’s most meaningfully aesthetic structures. In part, I am jealous of Paris and of Charlie Hebdo. The world mourns their losses and pledges to defend their freedoms, as it should. I only wish that St Louis and the tortured truths of ethnic and economic unrest that it now represents could have inspired a more perceptive cartoon to match its homegrown hybrid of Hebdo-Hoosier satire.