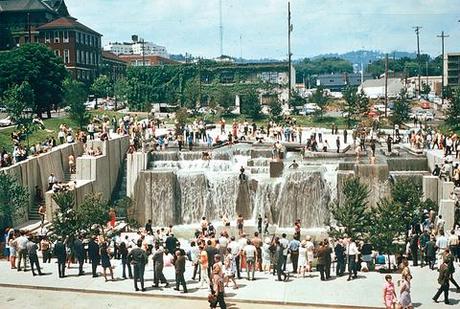

Architect Lawrence Halprin wrote of his Portland Open Space Sequence that he wanted the eight blocks of parks and plazas to contain "nodes for quiet contemplation, action, and inaction, hard and soft, yin and yang."

Philip Johnson famously quipped: “All architects want to live beyond their deaths.” Given the right scale and materials (think the Pyramids at Giza), that desired immortality can last at least a few thousand years. But designers have another opportunity for lasting greatness that is less reliant on size and slave labor: having their work listed in the National Register of Historic Places. This designation, overseen by the National Park Service, following approval by relevant state officials, has worked fairly well for modernist buildings, Johnson’s included.

Landscape architecture, however, has fared worse. In fact, fewer than 2,500 of the 80,000-plus National Register sites boast any significant landscape design. A few modernist icons have won this coveted consideration—Dan Kiley’s work at the Miller House and Garden in Columbus, Indiana, and Thomas Church’s minimalist design for the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan, were both listed in 2000—but most others have had

a hard time getting acknowledged.

Halprin in the mid-1960s.

A decade ago, Seattle’s Gas Works Park was rejected for designation because its landscape architect, Richard Haag, was still alive (an inconvenience in some preservation circles), leading the nomination’s reviewers to conclude that his career could not be fully assessed. This situation is not unique to Haag: Lawrence Halprin, who lived from 1916 to 2009, had none of his pioneering work listed by the National Park Service until 2010, when his Park Central Square in Springfield, Missouri, and Heritage Park Plaza in Fort Worth, Texas, were included.

Opinion about contemporary landscape architecture, however, does seem to be evolving. “Design icons, such as the Eames chairs and the Glass House, have helped solidify modernism’s significance among scholars and the public,” says historical consultant Charlene Roise, president of Hess, Roise and Company. “Now, with renewed interest nationally in urban centers and a growing understanding of landscape architecture’s value through projects like the High Line, modernist landscapes are also gaining awareness and supportive constituencies.”

Acquired by the city of Seattle in 1962, the site of Gas Works Park was used to produce gas and crude oil. Richard Haag’s 1975 design recast the industrial site as a grand park, replete with a play barn and picnic zones.

In November, Gas Works Park achieved a small victory when the state of Washington gave its approval for the 19-acre site, a brilliant synthesis of enviable topography and industrial heritage on the shores of Lake Union, to be considered for listing. Shortly thereafter, in January 2013, the park made the cut at the national level.

There’s more good news: M. Paul Friedberg’s previously endangered Peavey Plaza, in Minneapolis, a seminal project created in 1976 and a progenitor of the “park plaza” typology (a mix of American green space and European hard space), was also just listed on the National Register in early 2013. A national-level review is pending for Halprin’s stunning Portland Open Space Sequence—an intricately choreographed eight-block sequence of parks and plazas, created between 1966 and 1970 that recalls the nearby Cascade Range and Columbia River. In March, Arizona considers Garrett Eckbo’s Tucson Convention Center—a concrete abstraction created in the early 1970s and inspired by the surrounding desert and pine-covered mountains.

The tide is slowly turning for landscape architecture and its practitioners, especially as preservationists come to see that recognizing the designed outdoors can provide a more complete picture of modernism as a movement. And though it’s still too early to tell if these spaces will get the same consideration as the buildings, this recent activity is the start of a broader bid for immortality. —Charles Birnbaum