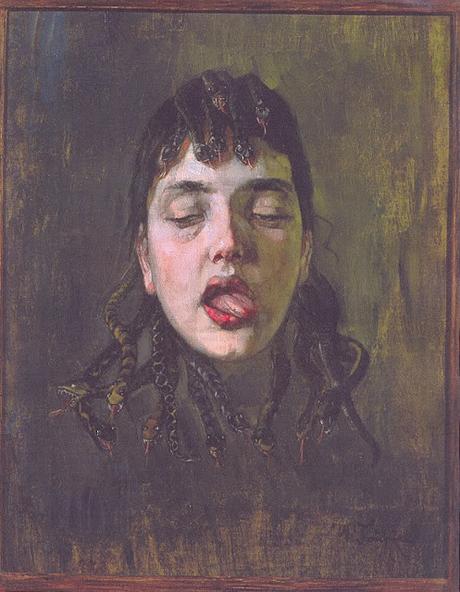

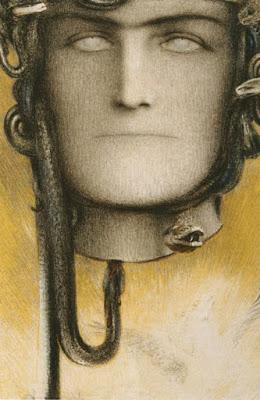

Medusa (1891) Wilhelm Trubner

Well, flipping heck.I don't know what disturbed me more - the snakes, the very odd eyes or the blood-stained, forked tongue. Yes, it's probably the tongue. Yikes. It was so far removed from the images of Medusa I was more familiar with, for example the Burne-Jones Perseus cycle...

The Death of Medusa (1882) Edward Burne-Jones

There is a graceful sterility to Burne-Jones' death scene, Medusa as pale as the stone figures she created, and Perseus and Pegasus both in tasteful pastel colours. There are no weird tongues or rolling eyes here, thank you very much.

Perseus and Medusa (1898) Frederick Pomeroy

I have been fascinated by Medusa since I was about four years old. I used to stay with a neighbor who had the Frederick Pomeroy figure as a lamp and I would stare at the severed head clasped in the naked man's hand while I ate fish fingers, wondering what on earth was going on there. Probably around the same time I saw Clash of the Titans, with Ray Harryhausen's spectacular Medusa hissing and rattling her way around her lair. Who could resist? Anyway, I got to thinking after seeing Trubner's gorgon, did any other artist share my fascination...?

Medusa (1895) Carlos Schwabe

I was not disappointed because there are a marvelous hissing bevy of Medusas, wiggling forth from the nineteenth century. Given the chance of portraying a woman with a head covered with snakes, I think we'd all jump at the chance. It can't help but be dramatic. I also don't think it's a coincidence that most of the images come from the latter years of the 19th century, around the time women were fighting for their rights, but I'll come to that in a minute...

Medusa (1867) Elihu Vedder

Perseus is a proper hero. He has a flying horse, he kills a vile monster and uses it to save a semi-naked lady from another monster. He then turned the rowdy elements at his wedding to stone too. That's pretty good going. Much of the portrayals of Medusa in the middle of the 19th century are based around her part in Perseus' story, mainly getting her head cut off.

Perseus and Andromeda (1874) Henri Picou

Often, poor old Medusa appears as second fiddle to the creamily naked Andromeda. Who's going to be looking at the severed head when there are perky boobs in the room? T'uh, typical. We've all been there, metaphorically, obviously.

Perseus Showing the Gorgon's Head (1892) Walter Crane

It would be very easy to keep Medusa as just an incident in someone else's story. She's like Excalibur, or the One True Ring, just the thing that denotes the greatness (or whatever) in someone else. What is interesting is that artists started to explore Medusa and her backstory. It's not pretty...

Aspecta Medusa (1860s) Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Aspecta Medusa (1860s) D G Rossetti

For ages I couldn't work out why this beautiful image of Alexa Wilding would have 'Medusa' in the title until I realised that she is actually Andromeda, finally being allowed to see the 'aspect' or face of Medusa, by bending over a mirror surface. Mind you, it did make me wonder if it is related to other images of Alexa as beautiful but evil women (such as Lilith), or some other part of Medusa's past. How exactly did she get those snakes? Had she always had such difficult hair?

Medusa (1896) Winifred Hope Thomson

Isn't that a beautiful painting? Not what you would be expecting from something called 'Medusa' but then the snaked-haired girl was not always a monster. Once upon a time there was a beautiful girl, according to Ovid, 'the jealous aspiration of many suitors' (Book 4 of Metamorphoses). On such suitor was Poseidon, who raped Medusa in Athena's Temple. For reasons best known to the ancients, Athena was so angry with Medusa that she transformed her into a monster that no man would ever want to look upon. Well, that's a Daily Mail level of victim blaming that takes your breath away.

Medusa Elihu Vedder

Suddenly at the end of the century, images of Medusa move from strictly monstrous to something other. Both Vedder and Thomson show beautiful women with qualities that leave you slightly uneasy. There is something in Thomson's smile that seems to hint at a secret, like the snake hiding in her russet hair. Vedder's woman has hair that is curling into snakes before our eyes as her face hardens. Maybe Carlos Schwabe's scream-queen above (very reminiscent of the Bride of Frankenstein, I thought) was based on the actual moment when the woman became the monster. It's a cruelty upon a cruelty, a woman at the mercy of two Gods, who destroy her because of their whims.

The Gorgon and the Heroes (1890s) Giulio Sartorio

The snakes are not specifically a part of the Medusa myth. In some versions of the tale, she remained beautiful and was just evil, like a siren, luring the cream of manhood to a terrible end. In some ways, snake-haired or red-haired, created or born, Medusa's grip on the fin-de-siecle had more to do with 19th century womanhood.

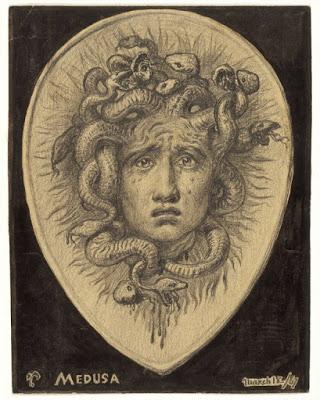

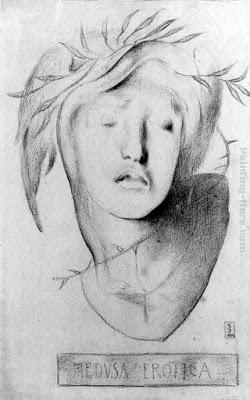

Medusa Erotica Simeon Solomon

By the end of the nineteenth century women were becoming monstrous. They were campaigning for votes, they were pushing out of their sphere, they were threatening the place of men. In times like this, I always turn to Idols of Perversity by Bram Dijkstra, who naturally touches on the subject and its sexual connotations. The snakes suggest the Garden of Eden and temptation. The rolling coil of snakes is both sexual and threatening, each fanged mouth biting at a tail, consuming and being consumed in a futile, lust-filled, hungry struggle. There is definitely the air of angry, destructive sex about Medusa. Often Medusa is portrayed as opened mouth, screaming. So many bitey mouths, no wonder men were worried...

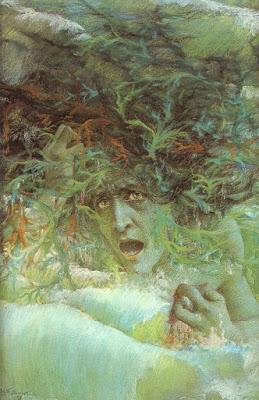

Medusa (1897) Levy Dhurmer

Medusa is seen as mad, destructive, angry, powerful and most of all unhappy. She is a woman crazy with power which seems to often cause her pain. Women shouldn't be powerful, it only makes them angry. Apparently. If you start giving women equal rights they go all weird and turn people to stone. Where will it all end. Probably kinder to outsmart her with a mirror and cut her head off. No woman can resist a mirror...

The Blood of Medusa (1898) Fernand Khnopff

Medusa (1878) Arnold Bocklin

There is a sorrowful quality in Bocklin's Medusa that I can't quite find in other depictions. Her head floats there, the snakes still wriggling, but she looks exhausted. Her expression is an echo of her traditional screaming anger, the mouth open, but it is pitiful. Compare that with Trubner right at the beginning of the post. Is Trubner's Medusa licking her own blood off her lips? For goodness sake.

Medusa (1909) Joseph Mullner

I suppose it is unsurprising that Medusa's head was a tempting subject for sculptors. It was a chance to make a life-size piece that looked both fantastic and true-to-life all at once. Mullner's snakes are especially life-like, with their oily-black coils of horror. Yikes.

Medusa (1900) Fernand Khnopff

Not exactly understated, Khnopff goes with more of a 'screaming' vibe for his severed head. I suppose the head did have the same treacherous potency after severing so there is no reason why poor Medusa would be allowed to be all peaceful and quiet. There is nothing human in Khnopff's imaging of her, either in 2D or 3D. On paper, he renders her a monolith, a hard-faced slab of evil, possibly echoing the stone she will turn us to just by looking at her. In sculpture, she is a dripping head of snakes, running like blood down the pedestal. There is no pity for her as she obviously would have no pity for us.

Medusa (1854) Harriet Hosmer

So what do we take away from Victorian depictions of Medusa? The image of a beautiful woman destined to be monstrous held possibilities. At what point did this beauty turn to evil, what happened to her, was it always in her? Women and snakes are so tightly linked, the potential of woman to bring temptation and destruction, that it is almost impossible not to read male fear of the growth of female emancipation. A woman can't have power without the corruption of men, a woman can't have power without the destruction of herself - the power in women seems to inevitably come at the price of everyone. Power is rationed apparently, if one gender has it, it must be at the cost of the other. Apart form men. men can have the power, that's all fine. Don't get any ideas about equality now, it will all end in tears.

To some, for example Burne-Jones, she is merely a part of a greater story, an episode on the way to a triumph. His Perseus cycle was painted during the decade after his affair with Maria Zambaco, a woman some found monstrous yet beautiful. Could it be read that Burne-Jones conquered his own gorgon in order to save his love? That is not a fair depiction of Zambaco and Burne-Jones' actions were not exactly heroic, but the sadness that colours the cycle could reflect his state of mind. For Georgiana Burne-Jones, the aspect of Zambaco in her husband's art was indeed horrifying.

Maybe it's no coincidence that some of Burne-Jones' best known pictures contain the head of Maria Zambaco, after all that's where the power is...