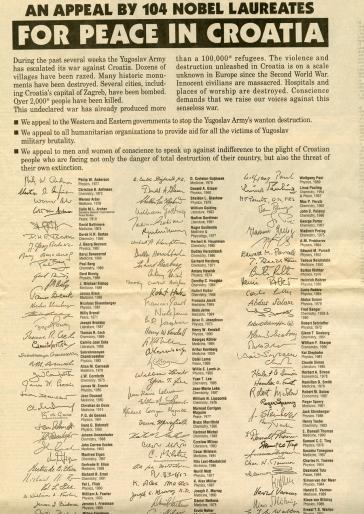

The New York Times appeal of January 14, 1992.

[Pauling and Yugoslavia, Part 2 of 2]

Three years after Linus Pauling’s 1988 visit to Yugoslavia, tensions in the country boiled over. Though it may have been justified in its desire to protect ethnic Serbs based on the atrocities that occurred during World War II, the incursion of the Yugoslav People’s Army into newly independent Croatia did little but add fuel to the conflagration.

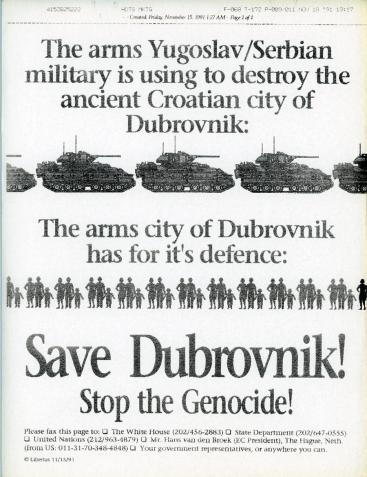

By the time a cease-fire agreement was brokered in 1992, several of Croatia’s major cities had been bombed and Dubrovnik, a city of major cultural importance, had been the target of several attacks. Even the institute where Linus Pauling delivered his 1957 lecture, “The Structure of Water,” came under threat of bombing in late 1991, as Serbian nationalists accused the institute of producing nuclear weapons.

As the conflict broadened, Pauling began collecting media reports and analyses. One article, published in The European and titled “Lies Within the Balkan War of Words,” claimed that Croatia was exaggerating minor conflicts with Serbs in the area while using the media to portray themselves as victims in the eyes of the world. Raymond Kent, an emeritus professor of history at U.C. Berkeley, had brought this article to Pauling’s attention while cautioning Pauling that he might be the target of Croatian propaganda efforts due to his recent travels and the awards that he had received while in Croatia.

Pauling’s response to this perceived threat was to lend his signature to the “Appeal for Peace in Croatia,” a document sponsored by a group called Truth in Croatia and published in the New York Times on October 11, 1991. Citing the deaths of over 2,000 people, with 100,000 more made refugees, the document appealed “to men and women of conscience to speak up against indifference to the plight of Croatian people, who are facing…the threat of their own extinction.”

Fax received by Pauling on November 18, 1991.

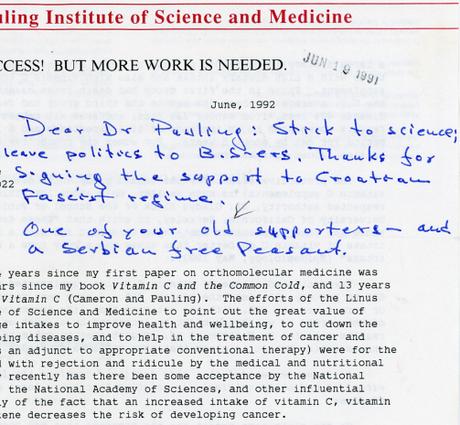

The October 11th appeal inspired both respect and reproach from those harboring an interest in the widening crisis in the Balkans. The Croatia-friendly nature of the document drew both skepticism and outright condemnation from a variety of critics. Probably the appeal’s highest profile signatory, Pauling received several letters from colleagues as well as members of the community who felt compelled to express their shock and anger. Many accused him of outright ignorance, often citing World War II and the atrocities committed by Croatians against Serbians during that time period.

Displaying the persistence that characterized his earlier peace activism, Pauling was neither intimidated nor did he show any signs that he was ready to back down. In a note to himself, Pauling described one encounter in particular with his old friend and colleague, Harden McConnell, and his wife Sophia.

Sophia gave me a good calling down for coming down on the side of the Croatians rather than the Serbians. Her main argument was that a century ago the Croatians were killing off Serbians. I said ‘well, why don’t we try moving into a new world instead of just going to war bombarding Dubrovnik?’

Harden McConnell, a former colleague of Pauling’s at Caltech and later a professor of chemistry at Stanford, frequently swapped papers with Pauling and had also stood by his side in protesting the Vietnam war. Likewise, Sophia McConnell had been close friends with Ava Helen prior to her death in 1981. That the McConnells disagreed with Pauling on the issue of Croatia did not seem to affect their friendship in the slightest. Notably, Pauling continued to nominate McConnell for multiple awards including, in 1993, the Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

Where the appeal was concerned, however, Pauling strongly felt that he was aligning himself on the side of peace, and he was not afraid to voice his opinion on the matter. Calls to see the other side and accusations that he was portraying a multidimensional issue from only one perspective inspired little in the way of a reaction. While this tenacity of vision was typical of Pauling, his comment to Sophia reflected a hope that Pauling had always maintained for the future.

A note to Pauling written on an LPISM fundraising letter and sent to Pauling by a donor.

Perhaps nourished by his focus on discovery in his scientific endeavors, Pauling approached his peace work with the attitude that the only way humanity might make up for past mistakes is by creating a future in which these mistakes are not possible. Though he received a fair amount of criticism for the one-sided nature of the Croatia appeals, the spirit motivating Pauling’s involvement had little to do with choosing sides. Rather, he was much more interested in emphasizing the need for a better way to resolve world conflict, and he knew that this process began with awareness.

Greeting card sent to Pauling by photographer Milena Sorée, November 1991. The affixed photograph was taken by Sorée in Croatia.

As time moved forward and more information about the Croat-Serb conflict became available, Pauling began to receive less criticism and more gratitude. Several U.S.-based correspondents, as well as multiple Croatians trapped in war-torn parts of Yugoslavia, sent Pauling their thanks. Some of these were form letters, simply addressed “Dear Sir” or “Dear Colleague” with Pauling’s name filled in. Many more, however, were personalized cards or handwritten letters recognizing Pauling’s contribution toward a peaceful resolution of the fighting in Yugoslavia. In certain cases, even people who didn’t agree with Pauling’s stance recognized his good intentions and commended his willingness to raise his voice in the name of peace.

Over time, new updates on the destruction in Yugoslavia came pouring in, as did requests that he “raise his voice again.” To this, Pauling responded by signing an even larger appeal, published in the New York Times and containing the names of over one hundred Nobel Laureates appealing for peace in Yugoslavia. Interestingly, only six laureates who signed had received their Nobel Prize for peace. Instead, the largest number of signatories had earned Nobel Prizes for their work in the sciences: thirty-four in physics, twenty-seven in chemistry, and another twenty-seven in medicine.

This second appeal, published on January 14, 1992, appeared on a full page of the New York Times shortly before a cease-fire between Serbia and Croatia was declared, the fifteenth in a succession of many unsuccessful attempts to stop the fighting long enough to negotiate a formal agreement between the two countries. In fact, the conflict within Yugoslavia did not see any form of resolution until the year after Pauling died.

A few months after the Nobel Laureate appeal was published, Pauling’s main contact in Croatia during his 1988 trip, Z.B. Maksić, issued a statement on behalf of the Croatian Pugwash group that capitalized on Pauling’s efforts to raise awareness. In the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Maksić asserted that “communism is still alive and well in Belgrade,” a suggestion that struck a nerve in the western world and solidified many western opinions on the subject.

In September 1992, the United Nations announced that it was expelling Yugoslavia until Belgrade recognized Croatia and Bosnia as independent nations, a statement that outraged Serbians. The conflict eventually came to a close with the Dayton Accords of 1995, at which the presidents of Bosnia, Croatia, and Serbia agreed on a generalized framework for peace in their troubled region.