A quasi-country gentleman of a player, who would command football’s classical heritage so as to lend an air of cultivated nonchalance to his pitch holdings, an astute real-estate developer—selecting sites central to the defense and often, as at Real Madrid, alongside the newly tamed waterways of a central diamond shape—and, finally, a functional architect who could play cheaply as well as grandly. That was Claude Makelele, the Palladio of modern midfield holders: ‘had he not existed, he would have to have been invented’. In a sense, he was invented. Had Real not drawn him out of the stoneyard at the dawn of a crucial tactical revolution, he would not have been Makelele, much less the pioneer of a Makelele-role. The times made the man. Luckily, the man was a genius.

nudus ara, sere nudus, ‘take off you coat, plough in person’ (Virgil, Georgics, 1.299).

Ancient writers who dealt with farm management such as Cato, Varro, and Virgil all described the peasant’s work as a task with deep philosophical and religious implications. Makelele was such a farmer and, like a Sansovino, he demonstrated his job’s effects in splendid palaces rather than in barn arcades. If he had been raised in the Tuscan tradition, he’d thought of his actions on the park in terms of separate blocks, while a Venetian would think in terms of visual continuities (consider the Cathedral area in Pisa in comparison with Piazza San Marco). A kind of urbanistic thinking prompted Makelele to draw together the discrete functions of the holding midfielder, sitting at the lower tip of a diamond, into a compact organism, whose ultimate metaphor is, as captured in this beautiful, Maori-like photograph, a muscular dance.

The antquarian’s nymphaeum at the Villa Barbaro, to remain on Palladio, represents more than the interests of other gentleman farmers—their interests producing the most richly and handsomely decorated sixteenth-century villa in north Italy—in so far as the marble image sitting on the upper level of the musty garden arcade, like Makelele at the height of his career as a deep-lying interceptor, contemplates a curved, rhomboid perspective that looks over a series of niches filled with stuccoed statues representing ancient gods and allegories (themselves fitting reliefs for the Real Madrid companions of that generation, a Figo, a Raul, or a Zidane).

The antquarian’s nymphaeum at the Villa Barbaro, to remain on Palladio, represents more than the interests of other gentleman farmers—their interests producing the most richly and handsomely decorated sixteenth-century villa in north Italy—in so far as the marble image sitting on the upper level of the musty garden arcade, like Makelele at the height of his career as a deep-lying interceptor, contemplates a curved, rhomboid perspective that looks over a series of niches filled with stuccoed statues representing ancient gods and allegories (themselves fitting reliefs for the Real Madrid companions of that generation, a Figo, a Raul, or a Zidane).

Behind this classicizing parade there was also a social theory of footballing history: midfield man, as embodied by the late Makelele, first lived and built alone, but later, seeing the benefits of commerce, he formed villages by bringing houses together and still later, cities by drawing villages together. By analogy, a holding midfielder would become more economical and natural a farm center as its functions were drawn together. More clustering, however, would not do.

A house is nothing other than a small city (Andrea Palladio, The Four Books of Architecture).

The theory behind the Makelele-role believed in a hierarchy of functions, and compared the lone holder’s dwellings to the ignoble but essential parts of the human body that the Lord ordained to be hidden from sight. The metaphor of the organism reminds us that every aspect of Makelele’s work was designed as if members were joined symmetrically to a central spine. Whether or not the shape was planned consciously to be built outward in symmetrical units from the spine—as against being raised all at once, storey by storey—this process proved to be eminently suited to the uncertain tactics of the time. The master’s dwelling had to be made habitable, but from there on midfield patrons added just what they could afford of the annexed loggias and towers. The tactical situation affected Makelele initially in determining his site. It dictated isolated areas rather than those where cultivation had gone on for decades: uninhabited delta and swamplands between the defense and the midfield where the chances for lucrative reclamation were good, and where newcomers could acquire large consolidated holdings. It also suggested building sites central to the reactive functions and a building programme that drew service structures and dwelling into a single man, despite what soccer treatises recommended.

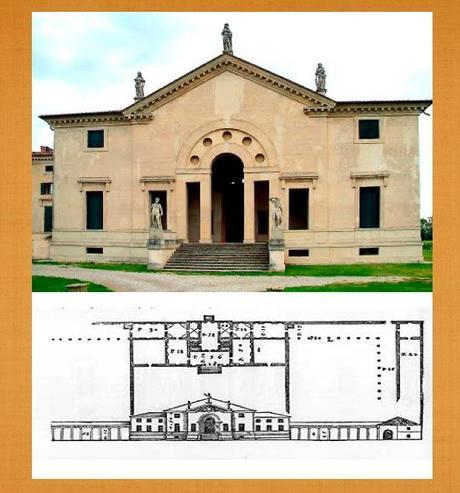

There are typological patterns among the teams derived from the original Makelele-shape: one has two banks of four—two major storeys and pedimented porches with open colonnades on both levels, as in the garden façade of Palladio’s suburban Villa Pisani at Montagnana, seen above. These types, which are all similar except that their porch is of one storey on a variable base of either low or high lines of defense, were not given extension for the services of a lone holding midfielder, nor were the attics designed for anything different than the grain storage accumulated by two strikers. How does this group differ in this respect? The sites are surely agricultural; perhaps the owner’s property was dispersed in small parcels, as sometimes happened, or the major area of cultivation was distant from the top of the league and less suited for success, so that barns and service structures would have been built out in the fields. (Palladio explained that the outermost blocks of four were designed for kitchens and storage functions, which usually were put in the basement, so the template may have been invented for swampy areas where everything had to be above ground level; hence the full two-storey elevation and the more vertical form of the block.)

Such spaces are rarely found in European football, where coaches plan for more than just two halls, one over the other, in the centre of the module. But in national tournaments, where even the simplest furniture becomes all the more majestic, many teams are taking advantage of this typological form, as if it had the grandeur of a Roman bath. The simplicity of this type is also economically determined; it is cheaper to limit classical ornament to a minimum.

Palermo’s mansions, for instance, are currently built of rough brickwork with a coating of 4—4—2 stucco. (More refined details were reserved under Delio Rossi’s tenure, when his president Zamparini showed so much exuberant taste and greater wealth that there probably would not have been enough sculptors to handle the building boom he had envisioned.) A man who is said, on an abstract level, to lack a certain physique du role and Zeman’s best disciple up to date, Rossi relentlessly pursues the fusing of run and soccer, whose apotheosis is in the musical figure of the fugue, in which melodic lines chase each other in varying patterns of reversal, inversion and repetition. His successor, by contrast, the Milanese Denis Mangia, is a witty fellow and has reverted to the articulation of Arrigo Sacchi’s structure, unfolding according to an internal logic of total football—a domestic architecture that is so cherished in Italy that even the etymology of the word, from domus, could not have been missed by Palladio himself.

Some time in the later sixteenth-century two extra bays were added to the façade, throwing the portal off-centre (J.S. Ackerman, Palladio).

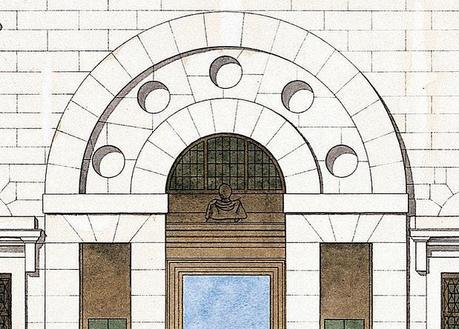

In the existing plans of other teams, however, there are signs that must represent a major departure from the original project of Villa Pisani at Montagnana. Without looking too disorderly, some rectangular elements appear to have been interpolated. Often, a clear-cut order of four columns in midfield was abandoned in favor of superimposed half-columns to achieve the kind of pictorial enrichment that has been a distinctive mark of Dutch football since Johan Cruyff and an early formula of Marcelo Bielsa’s Chile, too. (Sacchi came of age too early to allow the preparation of a new cut; maybe, as a client, he would have acquired the missing piece of property.) Probably many coaches calculated that two giant banks of four would be too dramatic for the narrow streets of domestic leagues, and therefore adjusted the scale of each soccer site by making the lower order equal to the actual width of the street. Unencumbered, in fact, by the parallel lining of players in groups of four, the middle of the soccer pitch offered distant and varied viewpoints in its ample squares. Almost a replica of what had been the original Makelele-role also appeared, making of a double-pivot the preferred system in the central tract between atrium and court—reminiscent of the tradition of Venetian palaces but already developed by Palladio in the entrance of Villa Poiana, seen above and below both in its draft and its shifting architectural form.

If one studies Palladio’s alterations of his own motive at Villa Poiana, and its hypnotic imbrication of the numbers 2, 3 and 5, it must come as a conclusion that the fanciful, domed arch in the uppermost section of the portal draws impressive attention, when put in soccer terms, to the space in front of the defense, a design function greater than in any previous tactical architectures, with the exception, perhaps, of the Pyramids of Cambridge, whose geopolitical origins are now discussed anew. No wonder the 4—2—3—1 system remained unfinished; it was not the technical house for the provincial gentleman, nor the footballing palace for a duke or a pope. The same is true of the accumulation of details toward its climax during the recent World Cup in South Africa, largely derivative of the soccer played by individual clubs. It is characteristic of the 4—2—3—1 typology to view the holding midfielder mostly in terms of superhuman grandeur. Inevitably, perhaps, since the ordinary shape had not been excavated in Makelele’s day. He saw things in imperial scale, even though he was practical enough to get his projects built for patrons of modest means as well. ♦