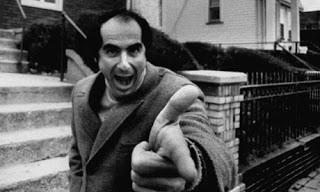

Let's rewind the clock to 1959. Philip Roth, at twenty-six years old, publishes his debut, Goodbye Columbus, a novella accompanied by several short stories. Though markedly genteel compared to his later work, Roth's portrait of Jewish-American ambivalence, with shared ethnic and religious backgrounds blurred by class and assimilation, generates controversy: some clerics even accuse Roth of anti-Semitism. Nonetheless, the book is a best-seller and critical darling, winning a National Book Award and establishing Roth as one of America's leading writers.

Let's rewind the clock to 1959. Philip Roth, at twenty-six years old, publishes his debut, Goodbye Columbus, a novella accompanied by several short stories. Though markedly genteel compared to his later work, Roth's portrait of Jewish-American ambivalence, with shared ethnic and religious backgrounds blurred by class and assimilation, generates controversy: some clerics even accuse Roth of anti-Semitism. Nonetheless, the book is a best-seller and critical darling, winning a National Book Award and establishing Roth as one of America's leading writers.After two forgettable novels, Roth creates an even bigger splash ten years later with Portnoy's Complaint. As if mocking Columbus's critics, Roth makes his hero, bureaucrat Alexander Portnoy, a masturbating mama's boy too self-obsessed to function as an adult. Its explicit sexual content, ribald humor and lacerating self-examination make it one of the most controversial novels ever: banned in prudish locales, condemned by many reviewers, yet instantly recognized as a literary landmark.

Naturally, Hollywood wanted a piece of Philip Roth, and both books made their way to the screen. As we've seen in previous articles, Roth is among the trickiest novelists for filmmakers to tackle: his prose style, self-analysis and overstated symbolism aren't easily rendered onscreen. Perhaps it would be best, after nearly a half-century of failures, for directors to leave well-enough alone.

Goodbye, Columbus (1969, Larry Peerce)

Put Larry Peerce's Goodbye, Columbus down as a nice try. A box office smash in 1969, it's mostly been forgotten despite launching Ali McGraw's career. It's enjoyable enough, competently rendering Roth's themes and story beats, if not quite capturing his voice or depth.

Put Larry Peerce's Goodbye, Columbus down as a nice try. A box office smash in 1969, it's mostly been forgotten despite launching Ali McGraw's career. It's enjoyable enough, competently rendering Roth's themes and story beats, if not quite capturing his voice or depth.Working class Neil Klugman (Richard Benjamin) lives with his aunt (Sylvie Strause), works a menial library job and dreams of breaking into affluent society. At a swank Jewish country club he falls for Brenda Patimkin (Ali McGraw), a spoiled New England heiress. The two begin a furtive romance, complicated by resistance from Brenda's class-conscious parents (Jack Klugman and Nan Martin) and his own reservations about Brenda's erratic behavior.

At times Goodbye, Columbus seems like a riff on The Graduate, with a post-grad slacker adrift in an adult world disappointed that he won't instantly succeed. Where The Graduate trades on the Generation Gap, Columbus makes class and identity its primary concerns. Arnold Schulman's script refines Roth's preoccupations, contrasting Neil's Everyman frustrations with Brenda and Co.'s posturing. The Patimkins are gauche social climbers, sloppily eating chicken and wearing gaudy clothes beneath their station; yet it's Neil, educated yet inexperienced, who earns their contempt.

Columbus frames these conflicts through its central relationship. Brenda acts like a WASP, alternately spoiled and tormented by her ghastly relatives and pretentious friends; she relishes sexual freedom while unable to think independently. She plays tennis and flaunts her wealth, even surgically altering her nose. She's intrigued by Neil, finding his crisp, witty directness appealing. Resenting his low station and lack of ambition, Neil comes to despise her shallow circle. Who, they ask through every word, glance and gesture, is this schlemiel to intrude on Brenda's suburban paradise?

Peerce's direction is scattershot: sometimes classy and discreet (through Enrique Bravo's deep focus camerawork), other times over-baked. He opens on a close-up of a woman's navel, followed by Neil leering at nubile pool-goers. Indeed, Columbus traffics in Ralph Rosenblum's exuberant, sexualized cutting, mixing romance with The Association's groovy score or Brenda's phony society. Occasionally this is effective, as with a poolside tryst; other times it clanks. The big wedding sequence, for instance, plays like caricature rather than commentary, contrasting a solemn Hebrew ceremony with characters scarfing down chicken liver.

Oddly enough, some of Columbus's weaker passages come straight from the novel. Contrasting Neil and Brenda's hookups with her brother (Michael Meyers) playing Ohio State's alma mater is painfully on the nose. And the odd subplot featuring a Gaugin-obsessed black kid (Anthony McGowan) generates only awkwardness. However iconic or tempting, some symbols are best left on the written page (see also The Great Gatsby's green light and billboard).

Richard Benjamin makes Neil tightly-wound and quietly resentful, making his character's indecision relatable. Benjamin managed a respectable acting career, though his greatest achievement was directing My Favorite Year. Ali McGraw shows an awkward, winsome charm utterly lacking in Love Story. Jack Klugman, Nan Martin and Sylvie Strause come dangerously close to cartoons; only Klugman finds moments of humanity, especially his heartfelt father-daughter chat. Bette Midler and Jaclyn Smith supposedly have bit parts, but good luck spotting them.

Portnoy's Complaint (1972, Ernest Lehman)

Considering that Portnoy's Complaint devotes whole chapters to its hero inseminating food, most wouldn't consider it movie material. Which didn't stop seasoned screenwriter Ernest Lehman (in his only directorial effort) from taking a wildly misguided, nigh-unwatchable stab at it.

Considering that Portnoy's Complaint devotes whole chapters to its hero inseminating food, most wouldn't consider it movie material. Which didn't stop seasoned screenwriter Ernest Lehman (in his only directorial effort) from taking a wildly misguided, nigh-unwatchable stab at it.Alexander Portnoy (Richard Benjamin) works as an aide to New York Mayor John Lindsay. Despite his prestigious title, Portnoy's driven mad by his psychosexual hang-ups. He relates his woes to a tight-lipped analyst (D.P. Barnes), relating the agony of his repressive parents (Lee Grant and Jack Somack), his ambivalence over Judaism and his fractious relationships. He finally seems to find happiness with the Monkey (Karen Black), the one girl who can satisfy his ravenous appetites. When the conversation turns to commitment however, Portnoy reacts predictably.

Since a faithful rendering of Portnoy's Complaint would be 101 minutes of ejaculation, Lehman dances awkwardly around the material, with results more perverse than Roth could ever dream. Having Alex describe his liver lust in loving detail manages, or pondering his emissions staining a girlfriend's rug, manages to be more disgusting than actually depicting it would be. It's depressing to consider Lehman, the writer behind North by Northwest and Sweet Smell of Success, putting time, thought and effort into Alex arguing with his mom about the contents of his stool.

At best, Portnoy is a dirty joke repeated third-hand: with all the action off-screen, it's reduced to endless, unfunny smuttiness. When Lehman isn't cannibalizing Roth's prose is inappropriate monologues, he's inundating us with childish fantasy cutaways (Alex dressed as a baseball player, orating in a synagogue) or crude stereotypes. The women are various flavors of misogynist nightmare, existing to pleasure or frustrate our hero (or, in the Monkey's case, both), while Alex's parents are grotesque nightmares. Even incidental gags are tacky and mean-spirited, like Alex and Monkey discuss sex before a pair of deaf ladies.

But Portnoy saves its most repulsive moments for the final act. Shamed by the Monkey, Alex buggers off to Israel and falls in with an Israeli girl (Jill Clayburgh) immune to his charms. The scene culminates in attempted rape, removing any sympathy our hero might have generated, before seguing to a pointless fantasy trial where Portnoy's confronted by his parents, ex's and a disembodied John Carradine. Then the movie abruptly ends, leaving that discordant note of despair hanging over a sour, nasty film utterly incapable of grasping its subject. At least we can enter John Carradine sentencing Portnoy to a limp dick into our collective memory banks.

Richard Benjamin, so charming in Columbus, becomes utterly loathsome: every line's emitted in a self-satisfied nasal whine, replete with leering double takes and hateful smirks. In the novel, Portnoy struggles to balance his public rectitude with his endless selfishness; film Portnoy's just a smug pervert, underlined by Benjamin's obnoxiousness. Karen Black tries to humanize Monkey, but her character's blend of sex talk and mournful monologues plays false. Other supporting players are beyond redemption, with Lee Grant vying for cinema's most annoying mom.

There are two other extant Roth adaptations (Elegy and The Humbling), but they're both based on terrible books so I'm happy skipping them for now. Sure beats expending time on more tone-deaf, misguided adaptations of unfilmable books.