[Part 2 of 2]

Upon learning about Linus Pauling’s lawsuit, the National Review responded by deliberately provoking him, publishing an article in September 1962 titled “Are You Being Sued by Linus Pauling?” In answering their own question, the magazine’s publishers pulled few punches in reaffirming the stance that had so angered Pauling in the first place.

We are (or so his lawyers tell us). And so are other well-behaved papers and people throughout the country. Professor Pauling…seems to be spending his time equally between pressing for a collaborationist foreign policy, and assailing those who oppose his views and who question whether this country can simultaneously follow Dr. Pauling’s recommendations and remain outside the Communist orbit. Dr. Pauling is chasing after all kinds of people….His victory signal is the check or two he has wrested from publishers – who may indeed have libeled him, in which case they should pay up; but who may simply have been too pusillanimous to fight back against what some will view as brazen attempts at intimidation of the free press by one of the nation’s fellow travelers.

This public response made it clear that the National Review’s founder, William F. Buckley, had every intention of fighting the lawsuit to its end.

At the time, Buckley’s response probably seemed ignorant to Pauling since he had already won a settlement against the Bellingham (Washington) Herald and was in the midst of a complaint against the Hearst Corporation that would result in his receipt of $17,500 in June 1963. A twist was soon to arise, however, that made a major impact on Pauling’s strategy as well as that no doubt contemplated by an untold number of other individual used to living their lives in the spotlight.

New York Times vs. Sullivan

Pauling officially filed suit against the National Review on January 17th, 1963. However, Pauling’s case against the magazine was delayed for over three years, until March 1966, for a number of reasons: the need for information gathering; Pauling’s receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1963; and Buckley’s running for mayor of New York City in 1965. This delay proved to be crucial as, in 1964 a landmark Supreme Court case, New York Times v. Sullivan, was decided.

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan is the United States Supreme Court case that ultimately enabled the media to comment freely on public officials without worry of being sued for libel, except in cases of provable “actual malice.” The decision established the definition of “actual malice” as a publisher knowing that a published statement was false or acting in reckless disregard of its truth or falsity at the time of printing.

From there, the burden of proof in a libel case was outlined as falling on the plaintiff, who was charged with establishing “actual malice” on the part of the defendant. Doing so is generally fairly difficult as there is often little evidence documenting the details of which a defendant was or was not aware. The Court handed down this ruling in order to protect the First Amendment and it proved to be hugely influential. Aside from cases like Pauling’s, New York Times v. Sullivan made a significant impact on the Civil Rights Movement as, prior to the case, media in many southern states were wary of reporting on civil rights abuses for fear of libel action.

The New York Times decision did allow for future case-by-case determination of identifying parties subject to the burden of proving “actual malice.” Importantly, the possibility of extending the Times ruling beyond public officials seems to have been suggested first (or at least very early) by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in Pauling v. News Syndicate Company, tried just four months after New York Times case.

Decisions made in Pauling’s lawsuit against the News Syndicate Company helped to establish a precedent of extending the New York Times v. Sullivan ruling from public officials to public figures. If his scientific work hadn’t done the trick, by 1964 Linus Pauling had certainly made himself a public figure through his prominent involvement in the international peace movement, to say nothing of two Nobel Prizes. In determining that the Times ruling applied to him as well, the courts began to expand the restricted definition of libel to parties outside of public officialdom, an evolution that proved very damaging to Pauling’s litigious streak.

New York Herald Tribune, April 20, 1966.

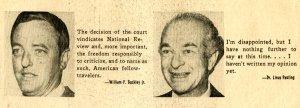

In March 1966 the National Review case finally went to trial in the New York State Supreme Court, but at this point Pauling had lost essentially all of his legal traction. The courts had already begun to apply the New York Times ruling to public figures and Pauling was unable to prove the new definition of “actual malice” against the National Review. As such, it came as no surprise when, in April, the New York court held that

The constitutional guarantees [of the First and Fourteenth Amendments] require, we think, a federal rule that prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement was made with ‘actual malice’ – that is, with knowledge that it was false or not.

Although Pauling was not a public official, the incident

would seem to favor extending the doctrine of that case at least to a private person who ‘has thrust himself into the vortex of the discussion of a question of pressing public concern.’…It is clear that if any private citizen has, by his conduct, made himself a public figure engaged voluntarily in public discussion of matters of grave public concern and controversy, Dr. Pauling has done so. Finally, the criticisms made of him in the alleged libelous articles are not criticisms of his private life; they are criticisms of his public conduct and of the motives for that public conduct.

Pauling understood the legal precedent weighing against him but disagreed with the Supreme Court’s stance on New York Times v. Sullivan – in effect, he felt that the tide of legal opinion weighing against him was itself fundamentally incorrect. Likewise, he objected to the court’s definition of “actual malice,” writing

I believe that the new criterion, as stated above, should not be upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States, because it places a reward on irresponsibility. I believe that the utterances of false and defamatory statements should be required by law to assume some responsibility, even though the false and defamatory statements are made about public officials or public figures.

Bruised by his National Review loss and disappointed by the New York Times verdict, Pauling actually contacted another lawyer, Louis Nizer, in hopes of finding a way to reverse the Supreme Court’s thinking on the standard of libel for public figures. Nizer, while pessimistic, agreed to initiate an attempt to get the public figures extension of the New York Times case overturned. Indeed, his firm appealed the case for three years, but ultimately conceded to the dismissal of its case in 1968.

In the wake of the bitter National Review saga, Pauling ended up either losing or abandoning all of the other cases that he had in motion. His legal power had been taken away by New York Times vs. Sullivan and, though often provoked over a lifetime that remained controversial, he never again mounted another libel case.

National Review, May 3, 1966.