There he was, Silvio Berlusconi in his velvet chair at the Lower Chamber, never some symbol or trope or a stand-in for any lofty ideal other than himself: a quite specific individual, in all his startling self-sufficiency. Inventing peace—improbably dapper in a navy-blue blazer, improbably calm for his last effort at trasmutation. The world was watching him through the lens of a camera that lingered on, while he scribbled three words of a memo, ‘8 traitors’ and ‘resignation’. (The automated eye of the machine was evidently supposed to be scanning the room.) And there he was, too, Luciano Moggi in the aquarium of bulletproof glass, while a panoply of lawyers and judges were rehearsing the deeds of Italy’s footballing Tutsis and Hutus.

In the legacy of sport grievances, Moggi was a man of whom terrible allegations had been made, and confirmed, and who was now going to have to face—for the first time stripped and deserted even by his former team—the perpetual endeavor to manipulate facts and fiction in a shuffling of papers and European defense tables.

I found myself being reminded of the moment in which the shattered prism of Yugoslavia went through the experience of the Tribunal in the 1990s, to end the historic cycle of vengeance and ethnic mayhem, even though the scene today looks like a farcical caricature of war crimes, and the prosecutor’s speech a nice bit of standoffishness like in Daumier’s etching.

Berlusconi’s tattered copy of himself flickered on the ramparts, while his followers were getting ready to surrender. The stock markets in Milan plummeted into pestilential marshes outside the parliament, on hostile territory. Everything was going wrong. The leader still retained control of his seething troops, but his stooped demeanor had the strained horror of Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt. Henry’s speech is imagined by Shakespeare like this:

Your naked infants spitted upon pikes,/ whiles the mad mothers with their howls confus’d/ do break the clouds, as did the wives of Jewry/ at Herod’s bloody-hunting slaughtermen./ What say you? Will you yield, and this avoid?/ Or guilty in defense, be thus destroy’d? (‘Henry V,’ III.3.90-96).

For years, Moggi’s haunting ghost had transformed Italy’ soccer landscape in one of those places where people seem uncapable of forgetting the past (and barely can think of anything else). Yet, Moggi was not a figure in the epic tradition; his actions were not in tune with the sense of history that James Joyce once characterized, in Finnegans Wake, as “two bloody Irishmen in a bloody fight over bloody nothing.”

On the contrary, Moggi was a modernist recast of Falstaff, in his sardonic attempts to steer his viewers clear of any depersonalizing approach—always trying to bluff his way out of a jam through the sheer force of his terrifying oratory.

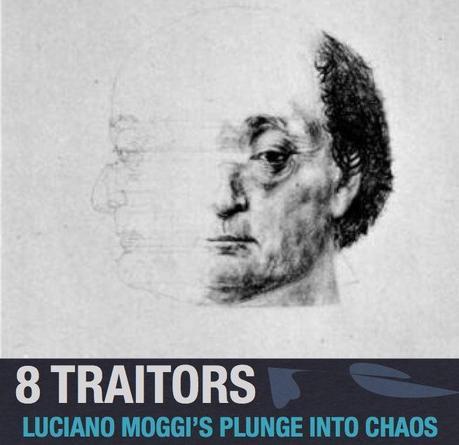

Far from believing that there were still ‘lion men’ and ‘lion days’ on his side, the days ahead looked to Moggi like monstrous excrescences of enormous chins, pitiful snub noses and deformed jawbones—the permanent traces of turning facial expressions among the people he courted and contorted while aiming for a rational pursuit. It must be because of Moggi’s reliance on the skeleton structure of laughter and deep inner recession that his case can be so well-explained by Leonardo’s method of physiognomics. There is an uncanny similarity between the motley underworld of referees and match-fixing in the Serie A and Leonardo’s insistence on grotesque heads and muscular pulls. “It is true enough,” writes Leonardo, “that some of these signs of the human face show the nature of their owners, their vices and their humors.” And so, like in a botanical study, passes along the terrestrial thickness of Moggi’s nerves and features: the bishop-ring marking the left pinky, cigar smoke through the nostrils, bags of black sleep in the eye sockets—and those horizontal lines across the bald forehead telling people the difference between brooding lament and bursting cheer, both bestial and irascible.

In the future, Luciano Moggi will perform all his wooing away from microphones, further away from journalists and their weaving webs of words. His gaze no longer engaging and bestirring of thought, he will not seek the darting look of a passerby or a girl from his town who cracks open a shutter and disappears.

A brain ravaged from the forces of power, Moggi can’t see beyond his hawkish nose, which those magnetized eyes of his fix on savagely. Beyond, there is Chaos. Will his jacket, which was once an electric shade of blue, still distinguish him from a crowd that seems smudged with charcoal? Clasping his fist among proletarian jeers, his features twisting in disgust at the society in which he lives, Moggi appears almost identical to the famous portrait of the late Duke of Montefeltro, who had himself hands glittering with merchandise and lowered, ox-like eyes to size up who’s present. Slumping the hours between the Way of the Cross and other numerous stations of the wine cellars, Moggi will perhaps outstretch his pain on the deck of his old age, pretending to be distracted or casting a scornful glance to the new soccer suppliers, which he mistakes for the oil-tanker of his youth. How true. It’s this being doubled over his burly body that tells him who he is. He knows in his heart that his friends are right in advising prudence. Yet at the same time he can’t help thinking that if he were a nightingale, his friends—for his own good—would be sure to dash his eyes out. ♦

More on Luciano Moggi: Juventus Sonata: Third Movement.