Directed By: Ivan Passer

Starring: Robert Duvall, Julia Ormond, Maximilian Schell

Line from this film: "I know what you say, what you do, who you screw. I know everything about you"

Trivia: To prepare for the role, Duvall watched hours of newsreels, read many books about Stalin and spoke to Russians who remembered him

In the early ‘80s, U.S. cable station HBO (short for Home Box Office) started producing their own movies, most of which premiered on the network. I remember watching Gulag, a drama / thriller starring David Keith, in 1985, while 1990 saw the release of two excellent HBO films: By Dawn’s Early Light, a highly-charged commentary on nuclear war; and El Diablo, a western comedy starring Anthony Edwards and Louis Gossett Jr that was co-written by the Horror Master himself, Mr. John Carpenter.

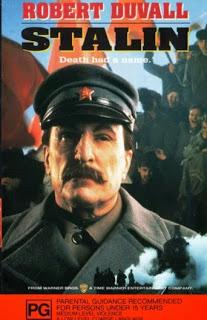

As good as these movies were, though, they paled in comparison (for me, anyway) to 1992’s Stalin, a dramatic telling of the life and times of Soviet premier Josef Stalin. With Robert Duvall in the lead role, and featuring an all-star supporting cast, Stalin is a tremendous piece of work, and has lost none of its power over the years.

Narrated by Stalin’s daughter Svetlana (played by Joanna Roth), Stalin takes us from the early days of the Russian Revolution, when the Bolsheviks, under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin (Maximillian Schell), overthrew the czarist government and took over a nation devastated by the war in Europe. The son of a Georgian cobbler, Stalin (Duvall), who was named the party’s General Secretary, wasn’t as well-educated as his fellow Bolsheviks, and was often at odds with Trotsky (Daniel Massey), a man many believed would be Lenin’s successor.

But when Lenin died in the early 1920s, it was Stalin who seized control. Fearing that someone might try to replace him, Stalin, with the help of men such as Molotov (Clive Merrison) and Lavrenti Beria (Roshan Seth), systematically purged the government, exiling Trotsky to Mexico and charging old comrades like Zinoviev (Andras Balint), Kamenev (Emil Wolk), and Nicolai Bukharin (Jeroen Krabbe) with “treason”, a crime punishable by death. With the communist party decimated, the military found itself ill-equipped to deal with Hitler’s Germany, which invaded Russia and, for some time, looked as if they were going to conquer the entire country.

Along with its lead’s public life, Stalin delves into his marriage to Nadya (Julia Ormond), a party secretary who experienced first-hand just how vindictive the man she loved could be; as well as his often-tumultuous relationship with his children, from his older son Yakov (Ravil Isyanov), who he treated harshly, to his daughter Svetlana, who was every bit as stubborn as her mother. By showing us both sides of the man (public and private), Stalin paints as complete a picture of its main subject as it possibly can, while at the same time revealing how his hard-nosed tactics and restrictive policies resulted in the deaths of tens of millions of his fellow countrymen.

Though it has an epic feel to it, Stalin is not a “big” film; for the sequences involving the Russian Revolution, director Ivan Passer utilized footage from such silent movies as Eisenstein’s October and Pudovkin’s The End of St. Petersburg instead of staging his own battles. That said, the movie does recreate the time period wonderfully, and with many scenes shot inside the Kremlin, Stalin also has an air of realism that works to its advantage. In addition, the film features some outstanding performances, including Maximillian Schell as the sickly Lenin, and Julia Ormond as Nadya, Stalin’s loyal but ultimately disillusioned wife who, realizing what her husband has become, takes matters into her own hands.

And then there’s Robert Duvall, who delivers a tour-de-force performance as the historic title character and brings the man’s strength and determination, as well as his cruel nature, convincingly to life (at one point, Stalin refuses to allow his son Yakov to marry a Jewish woman. Distraught, the young man rushes into another room and tries to shoot himself. The wound is not critical, and as Nadya is kneeling next to Yakov, tending to his wounds, Stalin stands just behind and says “That idiot. He can’t even shoot straight”).

We, like everyone else, come to fear Stalin, but as we see in this movie, Stalin was himself afraid of those around him, including the so-called “educated” Bolsheviks who he believed were conspiring against him. So, for protection, he surrounded himself with dolts and criminals, men who would carry out his orders without hesitation, and were as vicious as he was. It’s tempting to say that Stalin was a complex individual, but that’s not the person on-display in this movie. What we see is nothing more than a paranoid bully and a sadistic brute, and how Duvall managed to capture all this while, at the same time, convincing us there was also greatness in the man is a miracle in and of itself.